How a bad sanctions mix saved Putin

The price of misunderstanding economics

In March 2022, while Vladimir Putin’s blitzkrieg on Kyiv was failing, Russian markets were in free fall and financial panic was spreading. Ukraine’s allies had frozen the Russian central bank's foreign assets and expelled (most of) Russia’s banks from the SWIFT payment system. The goal was to trigger a financial crisis.

But the biggest source of revenue was left open. There was no full energy embargo. Not only did this decision grant Russia a continued source of income; it also neutralized the mechanism through which the other sanctions were meant to trigger economic collapse.

In 2022, Western leaders faced a choice on how to complement the financial sanctions. They could block Russia from selling its oil and gas to us (export sanctions), or block Russia from buying our goods (import sanctions).

Simple economic theory (“Lerner symmetry”)—which only holds in a long-run equilibrium with balanced trade— suggests that both would have the same effect. If imports are blocked, export sanctions would not be necessary since Russia would have nothing to buy with the dollars they would be getting for their oil. How convenient. For politicians facing voters worried about heating bills and gas prices, the choice was clear: block luxury, machinery and technology goods sales to Russia, not energy sales from Russia.

But the theory was wrong, and not just because of the evasion of the import sanctions (with Western complicity, as carefully documented by Robin Brooks). As economists Oleg Itskhoki and Elina Ribakova (2024) explain, this symmetry only works in the long run, under stable conditions. It breaks down during a short-run financial crisis — when sanctions needed to be most effective.

A toxic combination

Financial sanctions, like freezing assets and cutting off SWIFT, are designed to do one thing: starve a country of the foreign currency it needs to operate. They aim to create a dollar and euro famine.

However, they were paired with convenient, but incomplete, import sanctions. This meant freezing Russia's bank account, but at the same time forbidding it from going shopping for our goods. The import sanctions drastically reduced Russia's need for foreign currency. Demand for dollars and euros inside Russia collapsed, which is why the ruble, after an initial plunge, soared to record highs, ending the financial crisis completely.

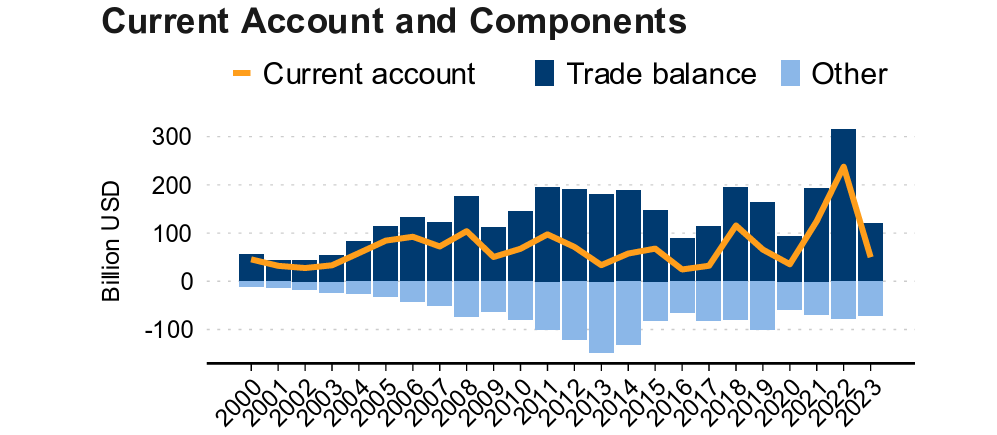

The mix created an unfortunate dynamic. Thanks to spiking energy prices, Russia was flooded with a record amount of cash — over $35 billion a month. Our sanctions ensured they could not spend it. The resulting record current account surplus stabilized the financial system when our financial sanctions were trying to wreck it.

The right complement for financial sanctions would have been export, not import, sanctions. Swiftly banning Russian oil and gas would have cut off their main source of income. The two sanctions would have worked together perfectly: one freezes the country’s bank account, and the other stops its paycheck. This double punch could have created the financial crisis that the West was seeking (Itskhoki and Ribakova, 2024).

The view from the inside

From our seats in the European Parliament, this mistake was frustratingly clear. Many of us saw the danger and fought for an immediate, total energy embargo. On April 7, 2022, the Parliament voted for a resolution calling for exactly that:1

an immediate full embargo on Russian imports of oil, coal, nuclear fuel, and gas…

At the time, we argued that the sharp pain of an embargo was politically tolerable, just as Japan tolerated the sudden shutdown overnight of all its nuclear power after Fukushima—a loss of 1/3 of the country’s total energy capacity. I worked with colleagues—France’s Raphaël Glucksmann, Belgium’s Guy Verhofstadt, Lithuania’s Andrius Kubilius and others—to push the case. I traveled to the Nord Stream pipeline terminal to protest its continued operation. In the port of Rotterdam, my team and I were briefly detained by port police for filming a Russian oil delivery — until they realized I was an MEP and politely but firmly insisted I join them for coffee instead in their boat. It is one of the enduring regrets of my political life that we collectively could do nothing to change the political calculus on sanctions of the only person who mattered then, Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

The price of delay

By the time the EU and G7 imposed a price cap and embargo on Russian oil in late 2022 and early 2023, the moment had passed. Russia had spent months building a ‘shadow fleet’ of tankers, finding new buyers like India and China, and creating new payment systems, to the point that its oil does not need to be greatly discounted to sell (see figure). What should have been a blow became a manageable problem.

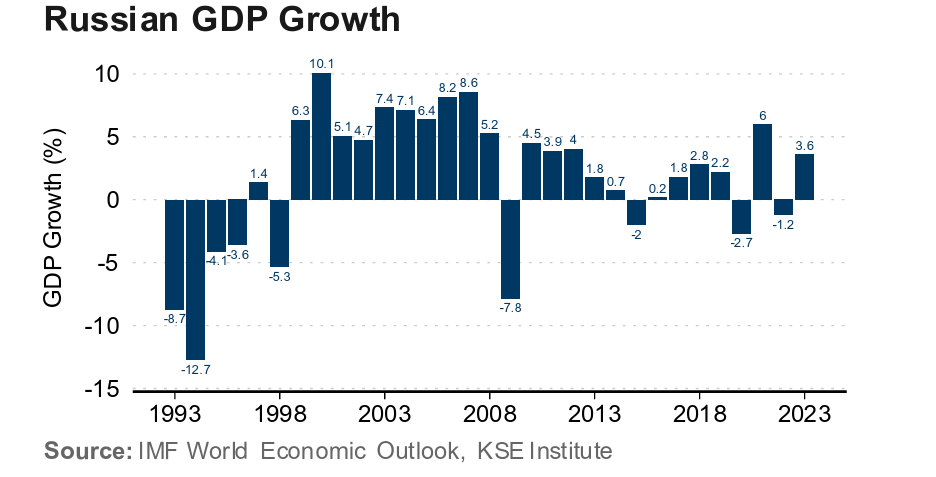

Fortunately, Russia's war economy is now starting to sag under the joint weight of the war and the sanctions. Official data put 2024 GDP growth at a good 4.3 percent, yet the drivers were one-off — emergency arms orders, lavish army pay, and a burst of state credit — and are fading. The IMF sees growth dropping to about 1½ percent this year, while private analysts predict even less.

Russia is running bigger deficits, of 1.5% of GDP in January to April. Crucially, oil revenue is down, as Russia’s Urals oil trades at near $65. The Central Bank of Russia’s main rate is at a painful 21% since inflation is near 8%. The latest sanctions package—aimed at the ‘shadow fleet’ and price-cap cheats — has pushed transport costs up and oil revenues down.

Russia, with an economy 1/10 that of Europe or of the US at the start of the war, is vulnerable. But as President von der Leyen and US Senator Graham meet in Brussels to patch up the leaky sanctions regime, we live with the consequences of that initial error. The economic pain Russia feels today was achievable in the first weeks of the war.

In future conflicts, we must remember the lessons of this sanctions debacle. Economic statecraft requires a clear understanding of how tools work in the real world, not just in simplified theory. In 2022, a misunderstanding of basic economics, fueled by political convenience, gave Russia the lifeline it needed.

References:

Itskhoki, Oleg, and Elina Ribakova. “The Economics of Sanctions.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (2024).

I proposed and negotiated this resolution. It was far from evident we would manage to get Parliament to vote on that phrase.

When European countries decided to supplement the financial restrictions already imposed on Russia with trade measures, the decision to act on imports/exports could have been simplified (passing the ballot to Mr. Lerner) to acting on imports or exports (one of the two). However, given the choice between one or the other, I believe that cutting certain EU technological exports—critical to the war effort—(imports from Russia) would have been more effective and efficient than cutting EU imports of Russian oil (exports from Russia), since oil is a basic energy commodity in demand on the world market (Russia could find many other customers, even if it had to settle for a lower price than that charged to the EU), while strategic EU technological exports to Russia would be much more difficult for Russia to acquire in markets other than the EU in this time of war.

No way China would have let Russia collapse.