Why Sweden has so many unicorns

Europe’s problem is not the lack of venture capital

Luis Garicano and Per Strömberg

I coauthored this post with Per Strömberg, SSE Centennial Professor of Finance and Private Equity at the Stockholm School of Economics.

The simplest explanation for Europe’s weak technology sector points to lack of capital, and in particular, venture capital. A recent open letter from a coalition of startups asked for ‘a European Venture Capital Initiative’. A recent IMF blog by Arnold, Claveres, and Frie concludes;

Europe’s shallow pools of venture capital are starving innovative startups of investment and making it harder to boost economic growth and living standards.

Europe, this story goes, lacks startups because it spends much less money on them than America. Give European entrepreneurs more money, whether public or private, and the gap will close.

But if we look at what explains the success of the more innovative European countries, the venture capital explanation doesn’t make much sense.

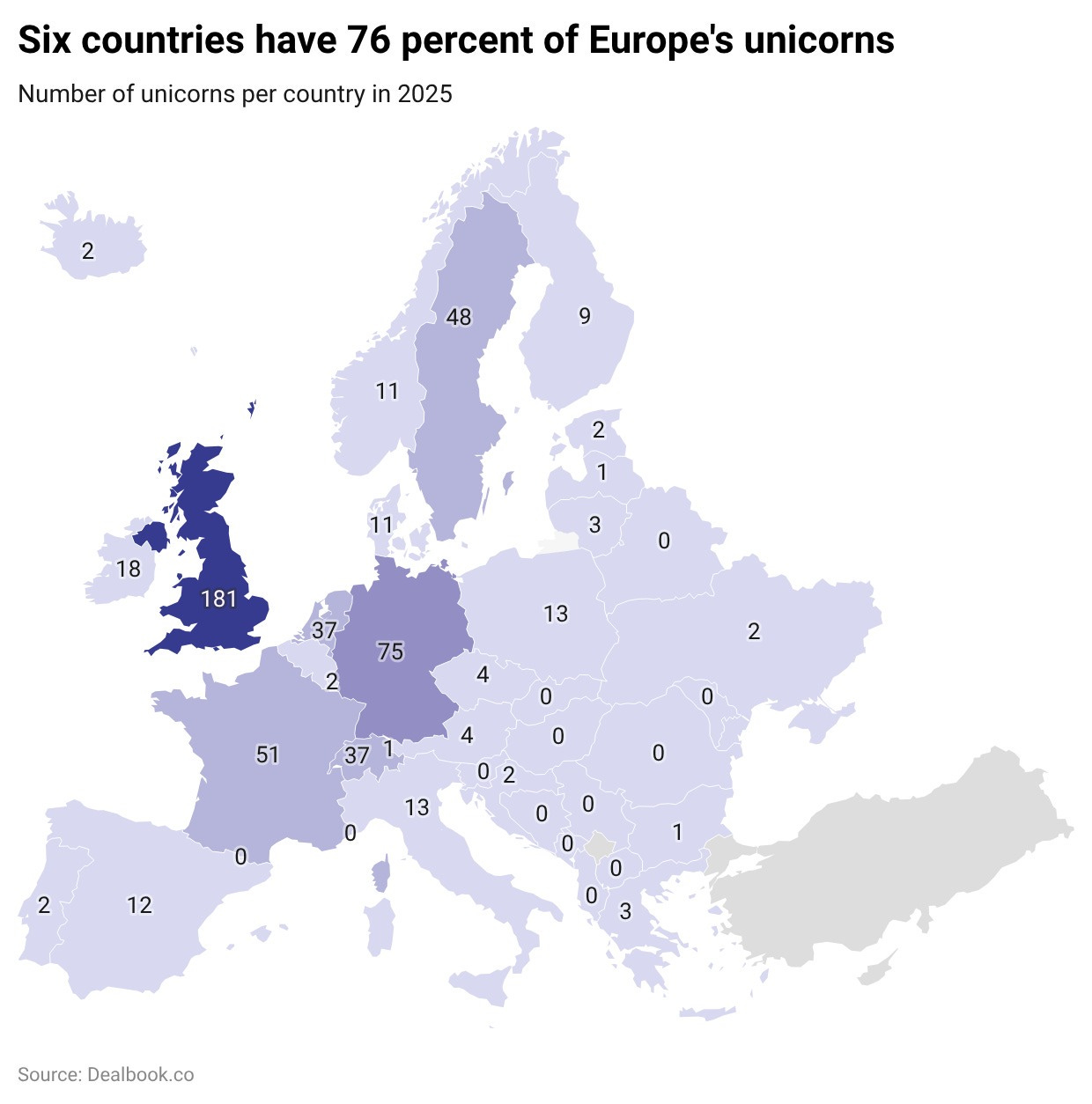

Sweden has ten million people and 48 unicorns (tech companies worth over one billion dollars). This makes it the country with the fourth most unicorns per capita in the world, behind only Israel, Iceland, and the United States. Stockholm itself produces more unicorns per capita than superstar cities like New York or London (but fewer than San Francisco). Sweden has the fourth most unicorns in Europe in absolute terms, only behind the UK, Germany, and France, countries with populations five to eight times larger. Italy’s GDP is more than four times Sweden’s, yet it has one-third of the unicorns, the same ratio as Spain, which has five times Sweden’s population and twice the GDP.

But most of Europe’s venture capital is cross border, and Sweden does not have access to a much larger domestic market for capital than Germany or France. The lack of venture capital activity in most of Europe is not a supply problem, but a demand problem: there are simply not as many promising companies for venture capitalists to invest in.

The reason is not that Sweden has a much greater supply of venture capital than the rest of Europe. It has a much greater supply of investable opportunities.

Venture capital is not the problem

European venture capital has grown dramatically over the last two decades. Europe’s share of global venture capital rose from roughly 5 percent to 20 percent by 2022, and the performance of European venture capital investments has not been noticeably worse than that of the US. The number of unicorns has surged, and entrepreneurial activity has spread beyond the old hubs: 65 cities across 25 European countries were home to at least one unicorn as of July 2023.

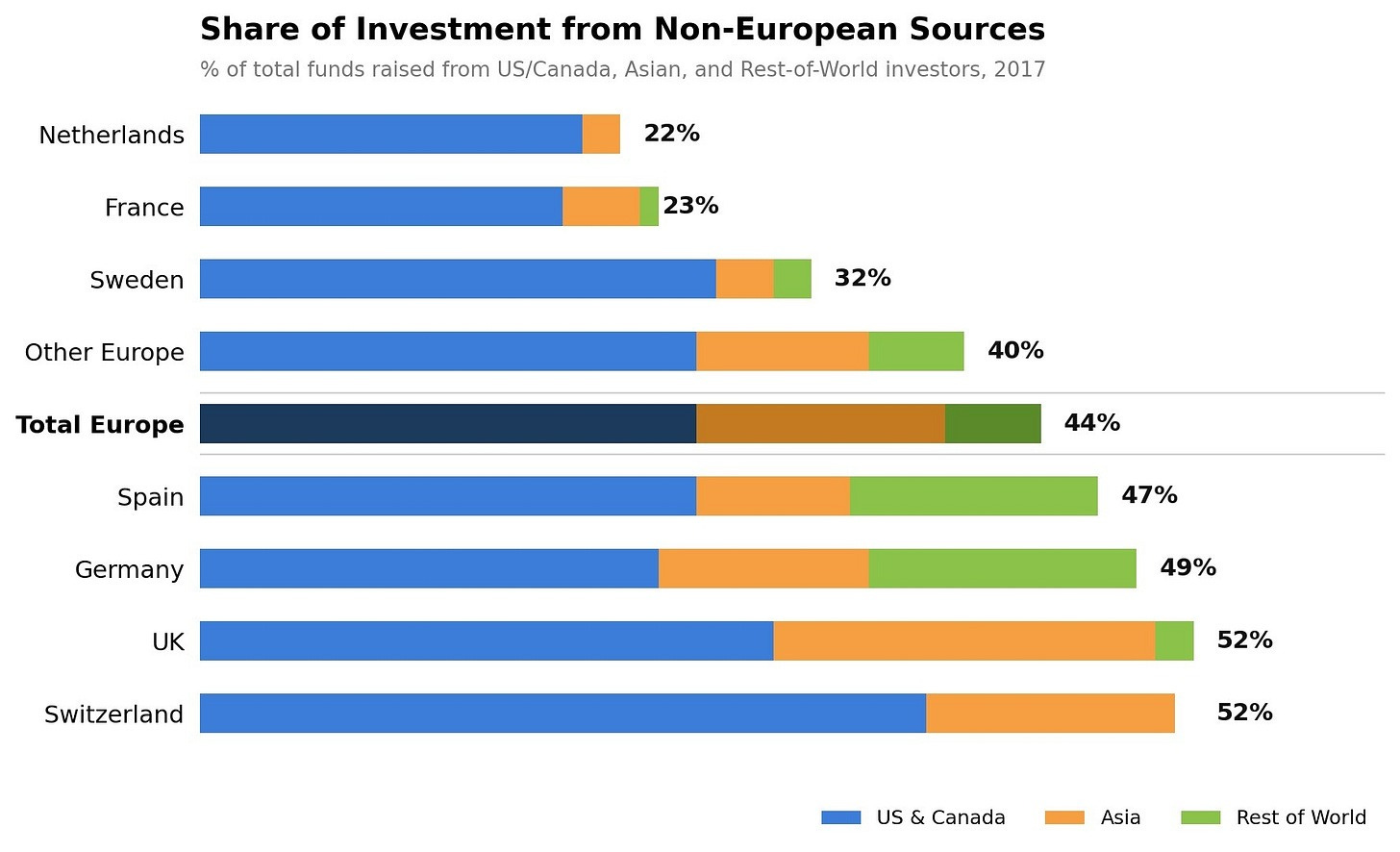

Venture funding for European startups has a substantial cross-border component, and US participation has increased over time. In Dealroom data summarized by Bradley and coauthors, 44 percent of venture capital invested in European companies comes from outside Europe. Cross-border reliance was especially pronounced in some national markets: in 2016 Austria, Ireland, Sweden, and Spain each received over 70 percent of venture capital investment from foreign investors.

Foreign participation is also visible in Europe’s largest rounds: by 2017 Europe had 17 rounds which raised more than €100M, and the paper notes that most included foreign investors, including cases such as Improbable (€502M, Japanese investors) and Farfetch (€397M, Chinese investors). Many of Europe’s most successful unicorns emerged in countries without large domestic venture capital markets, funded primarily by foreign investors. This means that if Italy or Spain had a pipeline of promising startups, the capital would find them.

But investable companies at the right stage are in short supply. To understand why, consider what venture capital funds actually look for.

What venture capital funds need

Venture capital funds have a limited life, typically ten years, during which they must invest, develop portfolio companies, and exit through a sale or IPO. Fund managers earn a fixed management fee (often 2 percent of capital) and a share of profits (typically 20 percent), amounting to total fees of 5–7 percent of invested capital. On top of this, since venture capital investments are illiquid, investors expect to earn a return roughly 2–3 percent above liquid investments.

To generate the returns their investors require, venture capital investments need to produce very high expected gross returns, on the order of 10 percent above listed equity when adjusted for risk. These returns also need to materialize quickly.

In addition, fund management exhibits increasing returns to scale, because many of the costs of running a fund, things like research, systems, compliance, reporting, are fixed or only rise slowly with size, and once a manager has built credible distribution in the form of relationships with platforms, advisers, consultants, and institutional allocators, the effort and expense of raising additional assets typically increase much less than proportionally. This makes it hard for new venture capital teams to raise a first fund, and pushes established funds toward later-stage investments.

The result is that entrepreneurs must rely on other sources of funding such as personal savings, informal capital and angel investors before they reach a stage where venture capital becomes viable. Without a pre-venture capital financing ecosystem, venture capital has nothing to invest in.

Sweden’s secret

Sweden’s success is that it does provide those investable companies. It does so thanks to a virtuous cycle built on angel investors.

Angels are individuals investing in startups on their own account. They have become the most important source of equity finance at the seed and early stages. In fact, there is now more early-stage angel financing than venture capital financing in the US and elsewhere.

Angels range from informal capital providers with limited wealth to ultra-wealthy individuals with entrepreneurial backgrounds. But only a few of these are actually helpful. An effective angel needs access to dealflow, the ability to screen investments, and the capability to add value through expertise and networks.

Sweden had a significant, but not astonishing, presence in the first wave of tech companies. But those alumni have gone on to found a huge number of new companies. Former employees of Spotify, Klarna, Skype, King and iZettle have built (and backed) a wave of unicorns, from finance and payments (Anyfin, Brite, Wise) and business software (Gilion, Stravito) to energy‑grid platforms (Fever) and new game studios (Resolution Games, Snowprint).

Part of this is due to a 2003 tax reform, where corporate tax on capital gains from selling shares in unlisted companies can be postponed as long as the proceeds are reinvested in other unlisted companies. Since Swedish founders and employee shareholders hold their equity through a corporation, this created a strong incentive to recycle proceeds into new ventures after a successful exit. In contrast, a broader tax incentive introduced in 2013 for individuals investing in unlisted companies has been largely ineffective.

Part of the problem with replicating Sweden’s success is that Sweden did not manufacture angel investors directly through subsidies. It needed the conditions (exit opportunities, tax incentives for reinvestment, a culture that treated serial entrepreneurship as normal) for successful founders to become the next generation’s backers.

Sweden abolished its wealth tax in 2007 and inheritance and gift taxes in 2005. It introduced the ISK (Investment Savings Account) in 2012, a simplified flat-tax vehicle that further increased household participation in equity markets. Swedish market capitalisation reached 169 percent of GDP in 2023, more than double the EU27 average of 69 percent (CEPS, 2025).

Investors in startups need to sell successful portfolio companies, and Sweden has deep, multi-tiered equity markets. Between 2016 and 2023, Sweden recorded 823 IPOs, the highest among EU member states, with nearly 90 percent on SME growth markets.

The Swedish government has occasionally invested in startups, but over time its participation has decreased. The participation of the Swedish government in total venture capital investments declined from 25 percent on average between 2011 and 2013 to just 6 percent in 2021. Saminvest, established as a fund-of-funds in 2016, has committed to venture capital funds and angel syndicates rather than investing directly.

Sweden benefits from a virtuous cycle where the founders and early employees of successful companies become angel investors, mentors, and serial entrepreneurs themselves. Guiso, Pistaferri, and Schivardi use Italian survey and census data to show that higher exposure to entrepreneurial activity in late adolescence predicts both entry and performance later on: a one‑standard‑deviation increase in firm density where someone lived at age 18 raises the probability of becoming an entrepreneur by about 1.5 percentage points and it is associated with about 11 percent higher entrepreneurial income.

What government can do (and has done)

Angel investor tax credits are widely used across Europe, but they rarely target experienced investors the way Sweden’s 2003 tax law did, and thus have little effect. Indeed evidence from tax credit adoption across 31 U.S. states suggests they mostly induced participation from investors who did not fit in the profile of engaged, expert angels. In fact, fewer than one percent of tax-credit recipients identify as professional investors. As a result, while the credits led to a one-fifth increase in the total volume of angel investing, they didn’t increase any meaningful economic outcome, including young-firm employment and job creation, startup entry, patenting, and the incidence of successful exits.

The lesson from Sweden is that Europe does not need more money for developed startups. If there is a case for government intervention, it is to provide tax relief to early, experienced investors in regions that lack them along the lines of the 2003 Swedish reform. Despite the cross-border nature of European venture capital, the first rounds do still typically come from locals.

If one must use the government to incentivize venture capital, there are a design principles that would make this less wasteful. Indirect government investment such as fund-of-funds that co-invest in new venture capital firms is more successful than government entities investing directly. Broad geographic and sectoral scope outperforms narrow targeting. And, requiring private capital to co-invest with public funds rather than the government being the majority investor is associated with better performance.

But there are no real shortcuts. Much of Sweden’s performance can be explained by experienced angels recycling proceeds from past exit. None of this can be conjured by a single policy or a new public fund. Like the Swedes in 2003, the parts of Europe that do not have start-up activity need to start putting these conditions in place today for a thriving entrepreneurial culture one or more decades down the road.

References

Axelson, Ulf, and Milan Martinovic, 2016, “European Venture Capital: Myths and facts.” Discussion Paper no 753, London School of Economics.

Bach, Laurent, Ramin Baghai, Per Strömberg, and Katarina Warg, 2023, “Who becomes a business angel?,” working paper, Stockholm School of Economics.

Bai, Jessica, Shai Bernstein, Abhishek Dev, and Josh Lerner, 2022, “The Dance Between Government and Private Investors: Public Entrepreneurial Finance around the Globe,” working paper, Harvard Business School.

Bradley, Wendy, Gilles Duruflé, Thomas Hellmann, and Karen Wilson, 2019, “Cross-Border Venture Capital Investments: What Is the Role of Public Policy?,” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12(3), 1-22.

Dealroom, 2023, “European tech ascendancy: Unlocking a continentʼs innovation potential,” Research report, Dealbook.co and Creandum. Available at https://dealroom.co/reports/european-tech-ascendancy (accessed 2/28/2024).

Denes, Matthew, Sabrina Howell, Filippo Mezzanotti, Xinxin Wang, and Tin Xu, 2023, “Investor tax credits and entrepreneurship: Evidence from U.S. states,” Journal of Finance 78(5), 2621-2670.

EIB, 2024, “European Investment Bank Investment Report 2023/2024: Transforming for competitiveness,” European Investment Bank.

EIF, 2023, “EIF VC Survey 2023: Market sentiment, scale-up financing and human capital,” EIF Research and Market Analysis Working Paper 2023/93, European Investment Fund.

Guiso, Luigi, Luigi Pistaferri, and Fabiano Schivardi, 2021, “Learning entrepreneurship from other entrepreneurs?,” Journal of Labor Economics 39(1), 135-191.

Kaplan, Steven, and Josh Lerner, 2010, “It ain’t broke: The past, present, and future of Venture Capital,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 22(2), 36-47.

Kaplan, Steven, Berk Sensoy, and Per Strömberg, 2009, “Should investors bet on the jockey or the horse? Evidence from the evolution of firms from early business plans to public companies,” Journal of Finance 64(1), 75-115.

Lerner, Josh, 2009. Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed – and What to Do About It. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Lerner, Josh, Antoinette Schoar, Stanislav Sokolinski, and Karen Wilson, 2018, “The globalization of angel investments: Evidence across countries,” Journal of Financial Economics 127, 1-20.

Lerner, Josh, and Ramana Nanda, 2020, “Venture Capital’s role in financing innovation: What we know and how much we still need to learn,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(3), 237-261.

Maurin, Vincent, David Robinson, and Per Strömberg, 2023, “A Theory of Liquidity in Private Equity,” Management Science 69(10), 5740-5771.

OECD, 2016, “The role of business angel investments in SME finance.” In: Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs 2016: An OECD scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Reshid, Abdulaziz, Ulrika Stavlöt, Peter Svensson, and Barbro Widerstedt, 2023, “Evaluation of the tax incentive for private investors in Sweden,” Working Paper 2023:01, Swedish Agency For Growth Policy Analysis (Tillväxtanalys).

Strömberg, Per, and Christian Thomann, 2024, “Real impact of private equity,” manuscript, Stockholm School of Economics.

Tax policy reflects what society values. If it values production and creation, it will exempt gains from production. If it values redistribution, policy will extract from producer and redistribute.

We should design tax policy to maximize production and minimize rent-seeking, which is why Land Value Tax is ideal, followed with Resource Rent Tax.

I'd argue here the importance of welfare has quite an impact in entrepreneurship in Sweden. If you know that, even if your idea fails, you won't end sleeping on the streets that helps you psychologically in taking the decision to move forward.