What a toad tells us about Europe’s housing problems

The commission can make it easier to build

I’m going to be hosting a small event on fixing Europe’s housing shortage in Brussels on the evening of November 18th (next Tuesday). It’ll be open to readers of Silicon Continent as well as any guests you want to bring. We’ll do a number of short lightning talks on housing followed by drinks. It’d be great to see some of you there. You can sign up here.

Berlin’s Pankower Tor development, as Fergus McCullough recently tweeted, is what Europe needs to solve its housing problems: two thousand homes in dense, livable perimeter blocks on what is currently a disused meadow besides a railway line. Along with the homes will come schools, offices, daycare centers, shops, high-speed bike paths, and a tram line. One third of the apartments will be affordable.

Unfortunately, construction at this site has been blocked since 2022, after the Berlin administrative court ruled that it was illegal to move the natterjack toads who live there. The natterjack toads have not been in Berlin for a long time: they only arrived in 1997, likely by riding along with a gravel truck. Only a few hundred of these toads live at this site. But, as they are listed in Annex IV of the EU’s Habitats Directive, it is illegal to capture or kill them, and, under Germany’s implementation of the directive, ‘significantly disturb’ them by ‘deteriorating the conservation status of the local population of a species’.1

In fact, Germany’s interpretation goes so far that they are not even allowed to move them across states. Instead, the court ruled, they must be protected on the site itself.

To fix this the developer decided to buy a nearby train shed and convert it into a habitat for the toads. Unfortunately, this too was blocked by the administrative court: the train shed requires historic preservation.

The developer then purchased a nearby allotment with plans to convert it into a veritable toad paradise with brush piles, artificial bodies of water, custom winter shelters, sand mounds, and three different types of stone piles.

The toad zoo fulfills the court’s requirement but the environmental group that had previously signed off on the development is now trying to block it. The chosen site contains a population of sand lizards — another Annex IV species — who the environmental group says cannot coexist with the toads.

The natterjack toads are causing more problems. The Obere Naturschutzbehörde (environmental authority) requires a planned storm drain in the development to first build a five hundred square meter magnetic pool that will attract and protect the toads. It has tentatively given the go-ahead for otherwise removing the species. The local environmental group is now suing to block that too. The project has been ongoing for over sixteen years. So far not a single shovel has entered the ground.

The natterjack toad problem may solve itself. The disused land is home to a growing population of willows, birches, and poplars. This makes the habitat unsuitable for natterjack toads, who dislike wooded land. The efforts of environmental groups to block the construction will likely guarantee destruction of the habitat.

There are many other cases where European environmental law blocks construction:

The German government recently created a pathway for local governments to give accelerated permissions to areas of undeveloped land adjoining built-up areas, which could be rezoned without a lengthy strategic environmental assessment. In 2023, the Federal Administrative Court found that this was illegal under the EU’s strategic environmental assessment directive, which allows plans to be exempted from these assessments only if it is ensured that these plans never have significant environmental effects — a criterion that makes any kind of blanket exception impossible.

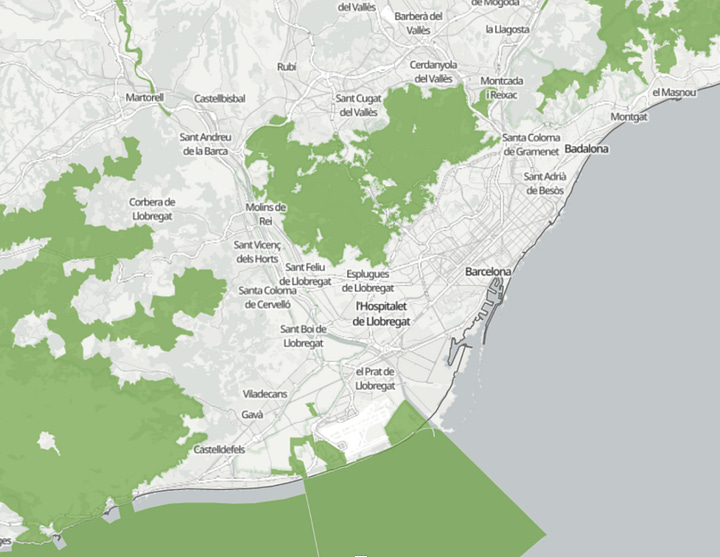

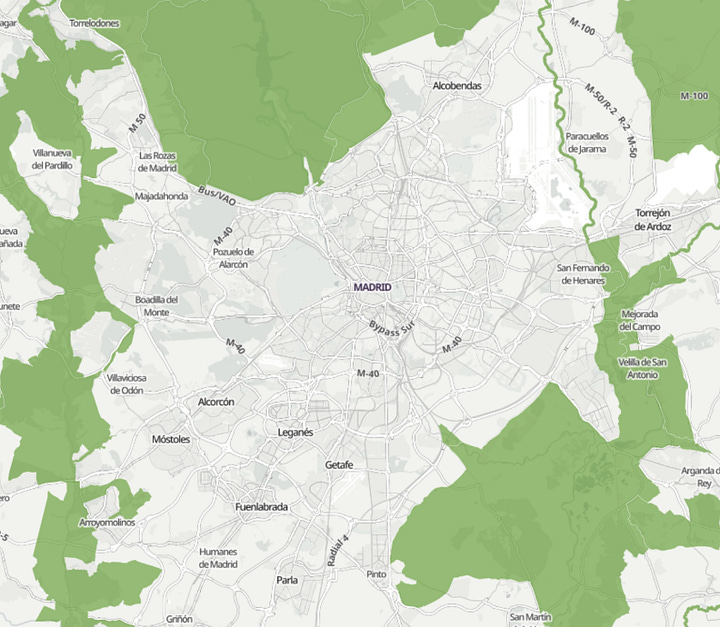

In Spain, the major cities Barcelona and Madrid are both surrounded by a belt of Natura 2000 habitats which will greatly constrain their future expansion. The Spaniards have de facto recreated the green belts that are at the heart of Britain’s much more extreme housing problems. This summer, a court blocked a project that was going to build 10.000 houses near Madrid after finding it was missing a specific European environmental impact assessment. A further 7.000 homes nearby are at risk as opponents try to use the same laws to block those as well.

EU habitats block the expansion of Madrid and Barcelona. In Ireland, courts have repeatedly struck down all kinds of construction for problems with environmental impact assessments (EIAs), which are mandated by EU law, including developments with hundreds of houses.

In Britain, which still has these European laws on the books, 120,000 homes were blocked in 2022 for violating nutrient neutrality mandates from the Habitats directive. It affects infrastructure as well. As part of a new high-speed rail line, a developer had to build a £100 million tunnel that would, in the most extreme scenario, save just 300 bats that were protected by the EU Habitats directive, at the cost of roughly £330,000 per bat life saved.

These are mostly examples of developments that were attempted and then still blocked. There are, presumably, many more developments that are not even attempted because developers understand that environmental law will block them. The Netherlands is the most famous example, where non-compliance with European rules around nitrogen emissions led the government to scrap most permits for new construction.

The solutions to these problems do not need to come at the expense of the environment. Europe’s environmental regulations are so poorly designed that with minor tweaks they can both serve the environment better and also enable more house-building, something I’ll dedicate a full post to in the near future. (Here are some smart ideas from Fergus McCullough.)

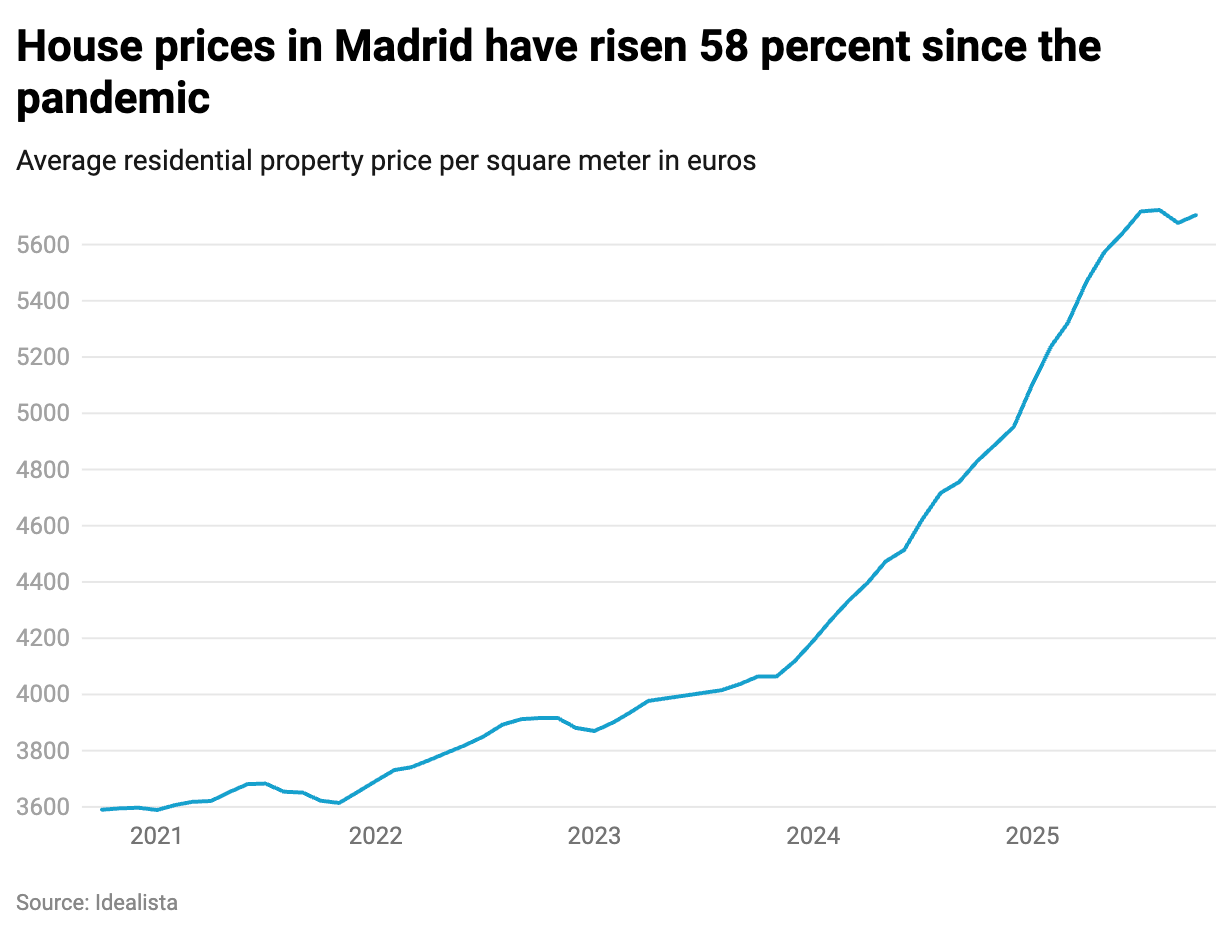

Housing is one of the central political problems in Europe. It was the most important topic for a majority of voters in last month’s election in the Netherlands, where the D66 party won with a campaign that promised to build ten new cities and its leader likes to be called ‘Rob the Builder’. Even countries with the highest number of homes per capita, like Spain, have seen steep price increases in recent years driven by rapid population growth, smaller family sizes, and people moving to superstar cities.

In her recent ‘State of the Union’, Von der Leyen dedicated a section to housing for the first time. The current proposals on the table are more of the usual: a ‘housing summit’ and a ‘European Affordable Housing Plan’; revised state aid rules to allow countries to subsidize construction companies; and restrictions on short-term rentals like Airbnb.

But in the many countries where the population is rapidly growing, like the Netherlands and Spain, and in the countries where many people can improve their circumstances by moving to more productive cities – the entire union – there is no solution that does not involve drastically expanding supply. The problems with environmental law mean the commission can do much more than it currently thinks.

The main issue here is Germany’s maximalist version of habitats, but the EU listing of the relevant species is what starts the problems.

The Berlin opening was funny! Wonderful writing. Could we get a novelist to expand on this?

A slightly more serious thought on Spain: Isn't Spain's problem that Madrid and Barcelona soak up the youth from the countryside? I recall an FT visualization showing population density changes across Spain. It reminded me of the depopulation of the French South that occurred some 100 years ago. The French have since corrected course, e.g., by making Toulouse the center of the European aviation industry. Similar efforts at industrial policy could also be great in Spain: Rather than expanding Madrid or Barcelona, Spain could direct industrial policy towards e.g., Galicia.

If I had a magic wand, I'd probably create a massive fund and give it to the regional universities to fund start-ups. Universities could then provide 80% guarantees on startup loans and take 10% equity or so. My take: We should be leveling up the regions to counteract the recent migratory pressures into the big cities. But it would be foolish to pick winners. Subsidized credit without many strings attached and light-touch regulation for building production facilities would go a long way. That would help agricultural and textile businesses in Galicia to expand, export, and bring good jobs—and workers—to a region that is less congested.

Not sure, on the other hand, that our energies are best spent fixing Berlin's problems. With tongue-in-cheek, note: Germany was well governed when Bonn was the capital. Decentralization is the answer!

very informative, keep explaining these very besic facts: judges entrusted with environmental regulations and laws will make development more difficult, if not impossible. they work hand in hand with degrowth NGOs. Quo vadis, Europe?