The Return of the Doom Loop?

Higher yields expose Europe's unfinished banking union

Ten-year US Treasury yields recently touched five percent for the first time since before the 2008 crisis. Given high debt levels, low growth, persistent inflation, and tighter monetary policies, it is quite likely that this shift towards high government bond yields marks a permanent break from the era of near-zero rates that defined the past decade.

This global trend strikes directly at the eurozone's core vulnerability: the sovereign-bank doom loop. During the eurozone crisis, a dangerous feedback loop emerged between banks and sovereigns. Banks held large amounts of their own government's debt. When governments faced stress, bank holdings lost value. When banks weakened, governments faced bailout costs, worsening the government’s position. Each problem amplifies the other.

Again, European governments accumulated massive debt during COVID-19 and the Ukraine war. As debt increases, borrowing costs rise and spreads widen against German bonds, the dangerous feedback mechanism between banks and sovereigns risks returning to center stage.

The EBA's Q4 2024 Risk Dashboard reported that EU/EEA banks' sovereign exposures increased by over three percent compared to Q2 2024, reaching €3.64 trillion, although the amount of exposure varies a lot between countries. For a concrete example: Italian banks hold sovereign debt equal to hundred percent of their core capital. If Italy defaults, these banks fail. Even if debt only falls in price (yields rise), banks balance sheets deteriorate (although accounting may hide that, as I explain below). Yet Italy supposedly guarantees these same banks' deposits.

Domestic financial sectors hold over fifty percent of sovereign debt in Spain, Italy, Germany and many other countries. Italian banks' exposure to domestic sovereign debt stands at almost twelve percent of total assets, while Spanish banks’ is over seven percent. These figures have grown since the pre-crisis period, particularly in peripheral countries where banks absorbed rising government issuance as ECB purchase programs ended.

The balance sheets and risk ratios do not reflect this risk, since all sovereign bonds are considered risk free assets. Here is Standards and Poors (2023) explanation:

Despite their preferential regulatory treatment, we believe sovereign debt holdings carry latent credit risk and potential market risks for banks. Our analysis of a sample of 70 large EU banks revealed that the incorporation of sovereign credit risk in regulatory risk-weighted assets would lead to an average depletion of the banks' CET1 ratios by 70 bps, all else being equal. For some banks, the reduced CET1 ratio could reach levels just above minimum regulatory requirements. Beyond that, sovereign debt portfolios carry interest rate risks, which banks need to manage carefully. In our bank ratings and, in particular, in our capital adequacy analysis, we routinely factor in sovereign debt holdings' credit and market risks, which explains the dispersion of our EU bank ratings to some extent.

Banking Union aimed to break this dangerous cycle through three pillars: common supervision, common resolution, and common deposit insurance. Banks would diversify their holdings across Europe. Deposits would be backed by European resources. The doom loop would break.

The first two pillars launched quickly. The Single Supervisory Mechanism gave the ECB oversight of large banks in 2014. The Single Resolution Board gained the power to close down failing banks in 2016, as long as they passed the “public interest assessment” (a political judgement that has proven an almost insurmountable barrier, except for the case of a mid-sized Spanish bank, Banco Popular in 2017 and for the subsidiaries of Russian Sberbank in Croatia and Slovenia in 2022).

The third pillar — European Deposit Insurance — never arrived. A 2015 Commission proposal died in committees. Without it, national governments still backstop their banks, and banks still load up on national debt. Any large crisis that engulfs a nation’s large bank will bring down the sovereign, and any crisis large enough to endanger the sovereign will bring down its banks.

This failure reflects a grand bargain that never materialized. Germany would accept collective deposit insurance in exchange for Italy accepting limits on bank exposures to sovereign debt. Neither reform occurred. The result: Italian banks remain captive buyers of Italian bonds, while German politicians protect their local banking fiefdoms.

The Sparkassen Problem

Germany's 359 local savings banks control €2.5 trillion in assets—making them one of Europe's three largest banking groups.1 Unlike normal banks, politicians openly control these institutions, since county governments appoint board members and committee chairs.

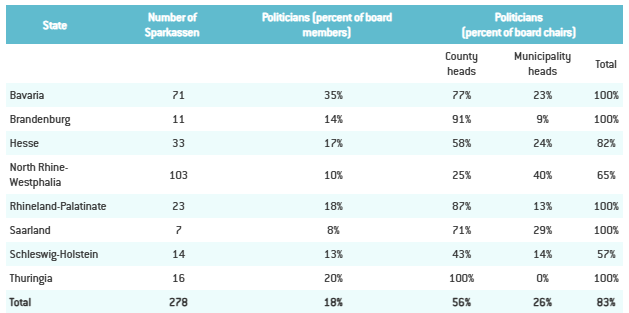

Véron and Markgraf (2018) show the extent of the entanglement between local savings banks and local politics: 82 percent of Sparkassen board chairs are elected officials. Most county executives chair their local Sparkasse. For North Rhine-Westphalia politicians who chair boards, Sparkassen fees average 12 percent of their total income.

This political control produces predictable distortions. Sparkassen increase lending by 1.5 percent before county elections—about €30 million per bank (Englmaier and Stowasser, 2017). There is no effect around state elections. Only county elections—where Sparkassen chairmen face voters—trigger the lending surge. These politically timed loans perform poorly, with profitability dropping immediately and defaults spiking three years later.

The system works through regulatory arbitrage. All but one Sparkasse (HASPA Hamburger Sparkasse) stay below ECB supervision thresholds, remaining under German oversight. Yet when marketing to depositors or credit agencies, Sparkassen present themselves as a unified €2.5 trillion network backed by an Institutional Protection Scheme, a risk-sharing scheme which pools resources across Sparkassen, Landesbanken, and other affiliated institutions. Fitch, for instance, rates them as one entity.2

This scheme is a fiction disguised as insurance. The IPS provides only that members be “ready for support.” Actual bailouts require 75 percent votes from rescue committees. The ex-ante buffer was just €4 billion in 2022—negligible against €2.5 trillion in assets. When Bayerische LB (a state or Kandesbank, but under the same IPS) collapsed in 2008, the Sparkassen IPS provided no capital. When NORD LB (also a Landesbank, again in the same IPS) failed in 2019, the process took months while states eventually absorbed part of the losses.3

The Sparkassen fear European Deposit Insurance. True insurance requires pre-funded, binding commitments. Political control would end. European supervisors would not tolerate lending surges before elections and defaults three years later. Four hundred politicians would lose their banks—and their 12 percent income supplement.

Rather than protect its sparkassen, Germany should heed the Spanish cajas de ahorros and US Savings and Loans disasters. Spain's cajas, controlled by regional politicians, held 50 percent of Spanish banking assets. Political control drove lending to favored constituents and construction projects (Cuñat and Garicano, 2009). When Spain's property bubble burst, the cajas required €60 billion in bailouts and helped push Spain into a sovereign debt crisis.

The American Savings and Loans crisis followed the same pattern (Romer and Weingast, 1991): small banks exploiting regulatory gaps while politicians, the system's main beneficiaries, refused to act despite known fragility. Political control appears harmless during good times but proves catastrophic when losses materialize.

The political constraints run deeper than German particularism. Governments want banks they can control during crises. Low-debt countries fear deposit insurance as hidden mutualization – German deposits bailing out Italian banks exposed to Italian debt.

But this reasoning is circular. Banks hold excessive home-country debt precisely because they operate within national borders. German banks hold German bonds. Italian banks hold Italian bonds. This concentration creates the mutualization risk that countries fear since, if the whole construction falls, then it will be (as in the Euro crisis) Europe’s problem

Breaking the Loop

A genuine Banking Union would break this pattern. Without regulatory barriers, true European banks would emerge with diversified holdings across the continent. These institutions could absorb individual member state risks without requiring that state's government support.

The Sparkassen makes this impossible. With €2.5 trillion in assets, 24% of business lending, and 250,000 employees, they carry political weight. When German top local politicians unite against European reforms, Berlin listens.

The eurozone built a monetary union without fiscal union. It created Banking Union without deposit insurance. These incomplete projects worked during the era of zero rates and expanding central bank balance sheets. In a world of higher yields and larger debt stocks, incomplete protection becomes dangerous exposure.

Meanwhile, Italian banks remain exposed to Italian risk, Spanish banks to Spanish risk. The next crisis will find Europe where it was in 2012: banks and sovereigns locked in mutual destruction, each able to destroy the other. In Cochrane et al. (2025) we explore some ways forward.

Thanks to Leo D’Amico, Christian Leuz and Nicolas Veron for comments on a previous draft.

References

Brunnermeier, Markus, Luis Garicano, Philip R. Lane, Marco Pagano, Ricardo Reis, Tano Santos, David Thesmar, Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, and Dimitri Vayanos. "European safe bonds (ESBies)." Euro-nomics. com 26 (2011).

Brunnermeier, Markus K., Luis Garicano, Philip R. Lane, Marco Pagano, Ricardo Reis, Tano Santos, David Thesmar, Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, and Dimitri Vayanos. "The sovereign-bank diabolic loop and ESBies." American Economic Review 106, no. 5 (2016): 508-512.

Cochrane, John H., Luis Garicano, and Klaus Masuch. “Crisis Cycle: Challenges, Evolution, and Future of the Euro.” Princeton University Press. Forthcoming.

Cuñat, Vicente, and Luis Garicano. "Did good cajas extend bad loans? The role of governance and human capital in Cajas’ portfolio decisions." FEDEA monograph (2009).

Englmaier, Florian, Till Stowasser, Electoral Cycles in Savings Bank Lending, Journal of the European Economic Association, Volume 15, Issue 2, April 2017, Pages 296–354, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvw005

Romer, Thomas, and Barry R. Weingast. "Political foundations of the thrift debacle." In Politics and Economics in the Eighties, pp. 175-214. University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Véron, Nicolas and Jonas Markgraf. “Germany’s savings banks: uniquely intertwined with local politics”. Bruegel 18 July 2018

Véron, Nicolas. "Europe's Banking Union at Ten Unfinished yet Transformative." Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 24-15 (2024).

A reader of a previous draft of this blog commented that “I suspect you underestimate the ECB’s current role in Sparkassen supervision. They look at the IPS because they supervise the Landesbanken, and they work on that together with BaFin – from what I can judge, more cooperatively than I would have anticipated. And of course they hold the license for all individual Sparkassen. My impression is that they had been very hands off in the first few years but things have changed a bit since then.” I would love to hear any comments on this from other readers.

According to Veron (2024) the supervisors (BaFin/ECB) were able to impose a much less conditional component of the IPS even though it will only be fully up and running in the early 2030s. See footnote 104 on page 76 .

Another solution would be to only allow narrow banking, so that all money in checking accounts needs to be backed by money (electronic reserves). If banks want to invest in other securities, like sovereign bonds, they would have to sell other instruments, for instance bond ETFs.

And the ECB could issue reserves backed by a basket of consumption-linked perpetuities, see here: https://gideonmagnus.medium.com/the-case-for-consumption-linked-perpetuities-in-the-eurozone-557779ece710

Do you think there is political will for a true Fiscal Union and Banking Union, or does the EU 'need' a new crisis, in other words for it to become 'Europe's problem' to act?