The failure of Macron

The supply-side reforms that weren't

On September 4, 2025, Jean Pisani-Ferry received a well-deserved Legion d’honneur for his service to France. In his acceptance speech, he offered a “funeral oration” for the project he helped build.

The program that brought Macron to power, designed by Pisani-Ferry, was an attempt to reform France by generating growth with supply-side reforms while spending on human capital and social transfers to manage the transition. The “right-wing” elements came first: the wealth tax was eliminated and labor law was reformed to introduce a level of “flexicurity”. This was paired with the “left-wing” €57 billion Grand Plan d’Investissement designed by Pisani-Ferry which focused heavily on skills training (a €15 billion investment), the green ( €20 billion investment), and technological transition (€13 billion).

The idea was to generate the economic dynamism required to fund the welfare state without having to dismantle it. It was a gamble that modernization could outrun the demographic crisis. The ungovernability of France and its low growth are evidence that this program failed.

One view of this failure, echoed in major newspapers like Le Monde, the New York Times, and The Guardian, is that Macron’s crisis is a crisis of free-market beliefs. Pisani-Ferry spoke of a rightward shift:

I soon realized that the balance between ideas from the left and those from the right gradually shifted … Those who, like me, had committed to a project of emancipation and equality under the law found it hard to recognize themselves in the government’s policies.

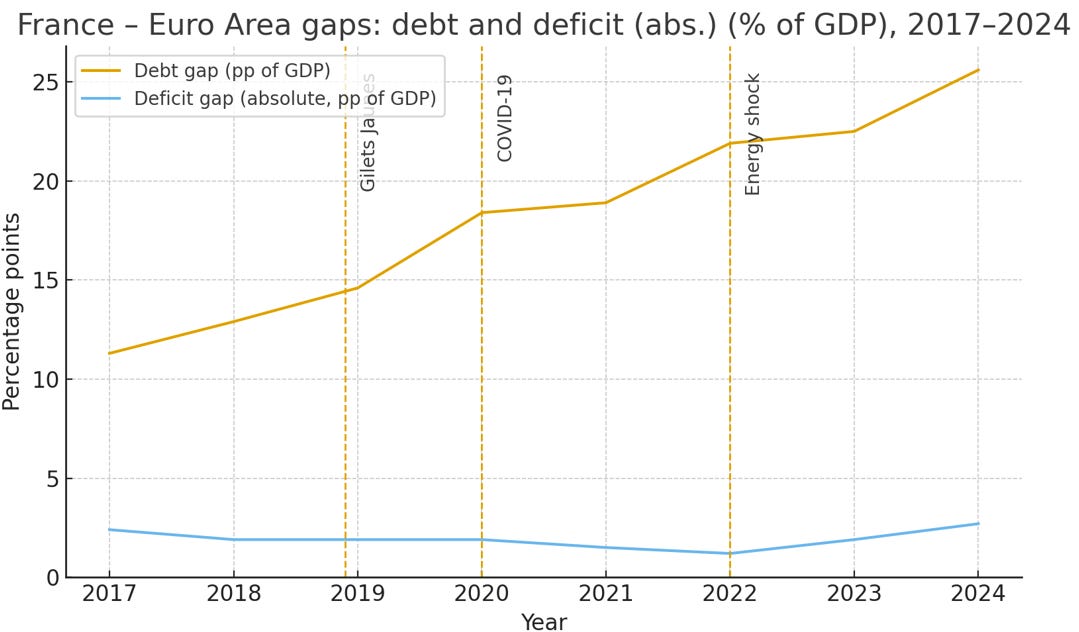

The fiscal record (see the figure below) contradicts any claim of retrenchment: after a brief effort to get the house in order in 2017 and 2018, Macron’s presidency was far from prudent with spending.

But so does the regulatory record. Labor markets were liberalized, but most other economic activity is more restricted now than it was ten years ago. It is harder for the French to build houses, build infrastructure, sell software, or generate energy. Thanks in part to Brexit, this same restrictionism has set the tone in Europe for the last decade as well. Contrary to what is commonly said, the cumulative impact of Macronism was to reduce supply rather than to expand it.

The record

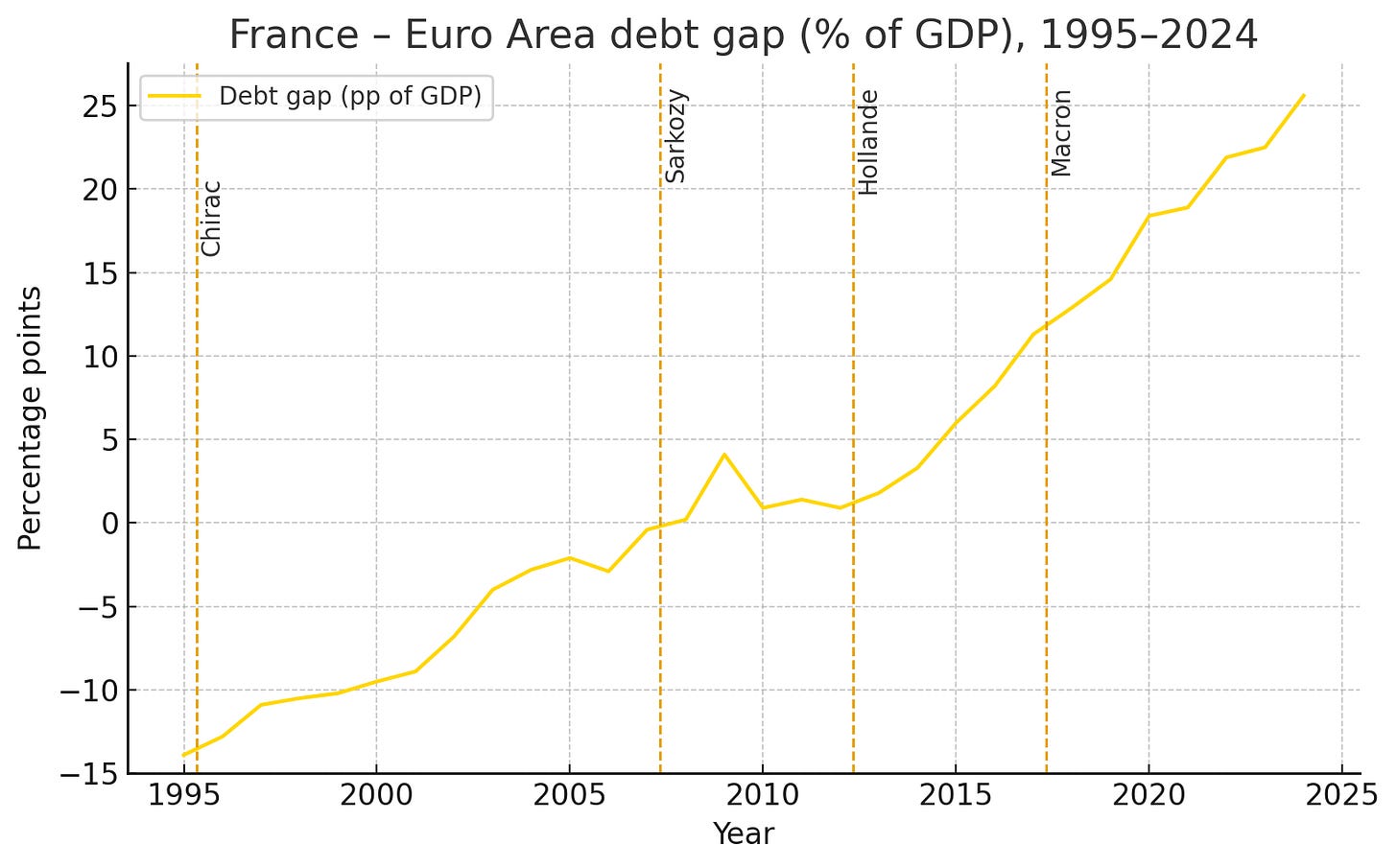

Macron’s government consistently spent more as a share of total output than any other OECD member, with the public sector accounting for over 57% of GDP in 2024. The telling trend is France’s divergence from its neighbors. When Macron took office, France’s debt-to-GDP ratio was 11 percentage points above the Eurozone average; by 2024, that gap had increased to 25 points. Public debt is set to hit 116% of GDP in 2025 and the deficit is set to double the EU average.

France’s fiscal stance under Macron reflects continuity with recent trends, rather than any break with the past. The Stability and Growth Pact sets a 3% deficit and a 60% debt reference. Since 2002, France has breached the limits every year, and the deficit limit every year except two.1 More telling, France’s deficit has exceeded the Eurozone average every single year since 2002. Its public debt has grown faster than its peers’ since 1995, with only a brief pause under President Sarkozy (see chart below).

An early attempt at fiscal prudence ended with the Gilets Jaunes protests in autumn 2018. A modest, ecologically-motivated increase of the fuel tax angered la France périphérique. The mass protests that first broke his presidency were tellingly not against a liberalizing policy, but against government actions that made life and economic activity more costly.

The government quickly capitulated. On December 10 of that year, Macron announced a €10 billion package of concessions: an increase of the monthly minimum wage, the abolition of taxes on overtime, and the cancellation of an increase of taxes on pensioners.

The model adopted during the Gilets Jaunes crisis has been the default mode of governance for much of the rest of the presidency. 2018 created the precedent that any shock would be met with the firehose rather than reform. It found a zenith during COVID-19 with the slogan “quoi qu’il en coûte”. The shock to energy prices after the Russian invasion of Ukraine was met with €100 billion to freeze consumer energy prices.

The supply-side reforms that weren’t

The story is the same at the microeconomic level. Whatever room his labor laws created was outweighed by a larger wave of government intervention elsewhere. The triple objectives of the environmental transition, digital regulation, and strategic autonomy led to a wave of new restrictions which weakened the ability of firms and people to build and innovate.

Housing is one extreme example. In 2021, Macron signed a law that commits France to zero net land development by 2050 (and half by 2030), making it illegal to develop any land in France unless some existing city or village is demolished. His governments banned renting less-well-insulated homes, allowed councils to forbid building second houses, and imposed nation-wide rent controls.

Brexit spread this trend toward state intervention across Europe. Britain was central to the EU’s traditional equilibrium; its departure weakened the faction opposing French “dirigisme”. Macron’s personal appointments, commissioner Thierry Breton and Ursula von der Leyen, weakened state aid rules and led the push for the Green New Deal and the digital agenda.

Dirigisme, not liberalism, was the goal from early on. In 2021, Macron argued:

We must rebuild the framework for a productive independence for France and Europe... This means that for the first time in decades, the state and public authorities are re-assuming a clear and simple strategy, not to plan everything... but to define the major strategic sectors where we need to invest.

Many of the objectives of the green and digital agendas were valuable. Yet the method for achieving them favored mandates over markets and prices. Across a swathe of the economy, mandates have created what are de facto infinite marginal taxes on activities that are often still valuable. Rather than pricing emissions from cars, the EU banned their sale from 2035. The 2024 Nature Restoration Law imposes quotas to restore 20% of all EU land and sea areas by 2030. This model is also the foundation of the digital regulations— GDPR and the AI Act — which operate through mandates and compliance targets.

None of these laws were designed to take into account the costs and benefits of the prohibitions: as mandates, they restrict activity even when the upsides of flexibility would be greatest. It could be the case that the last 20% of ICE cars are in places where electricity infrastructure is non-existent, which would lead people to want to keep old, dirty cars for decades. A price-based system would avoid this outcome. The current “no gasoline cars sold from 2035 onwards” does not. Europe’s defense industry is held up by environmental laws despite its existential importance.

Macron’s failure could be a defeat of the values that people commonly associate with “neoliberals”: cosmopolitanism, a degree of comfort with inequality, belief in institutions, and openness to the rest of the world. It is not, however, a defeat for freer citizens in freer markets—ideals Macron never truly embraced. He governed as a dirigiste in the tradition of De Gaulle, aiming at modernization through state intervention. His mandates will ultimately made it harder, not easier, for France to build and grow.2

Since 2003 France has only been below the 3% threshold cleanly in 2006 and 2018. In 2019 the headline deficit was 3.1% but INSEE classifies part of this as a one-off accounting change, hence Eurostat lists an adjusted figure of 2.4%.

Personal note from LG: I want to note that this pains me greatly. My admiration for Emmanuel Macron is sincere and dates back to our first meeting in Ciudadanos’ European Parliament offices in October 2016, when he was still a candidate. I have met him several times since, and on each occasion, I have come away convinced of his honesty, his good intentions for France, and his deep understanding of the challenges the country (and the world) faces.

I like the Brexit reading as the UK acting as counter-balance of European "dirigisme." However, the post-Covid world is heavily oriented towards a dirigisme of any kind (and any level), and even the late Tory government wasn't saved from this - let alone current Labour government. So, making a counterfactual of a non-Brexit scenario (in post-Covid era) is perhaps more difficult than it seems, I believe.

Macron is the exaggerated expression of an EU trend. The high level of dirigism in the EU political center is not discussed enough. I believe it comes more from incompetence, inefficacy, and disconnection from reality than from a conscious political choice. It is easy to write a piece of paper ordering the world you want - and not check whether it can exist. This has been the only EU policy for 25 years despite all the signs nothing was working.

My favourite quote from Jean Pisani-Ferry: “Je ne sais pas ce qui s’est passé”.

It describes a whole generation of leaders and advisors who decided they were right and never looked again.

Great post by the way.