The Auto Omnibus

Growth still comes last

We saw some exciting headlines last month about the end of 2035 ban on combustion engine sales. It is good for the things Europe is good at to be legal.

But the proposed amendment isn’t much better. The current ban requires the average emissions of a carmaker’s new vehicles in 2035 to be 100 percent lower than the 2021 level. The proposed rule lowers this to 90 percent. (So far, carmakers have reduced emissions by just 7 percent.) The additional emissions allowed by the new rule must be fully compensated with green steel and renewable fuel credits.

In a sense, this change is in line with what we have advocated on the blog. Some uses of a given technology are very valuable and therefore costly to abate. In order to discourage other uses but still allow those, policymakers should use taxes rather than a ban.

You can debate whether a level of tax is too high or too low – in this case, a tax for 100 percent of the remaining emissions after a 90 percent reduction still seems quite steep – but a tax is in any case much better than a ban.

But in another sense, this isn’t actually that kind of tax. Instead of buying compensation credits on the marketplace, automakers are forced to obtain them by actually using ‘Made in Europe’ green steel and by using renewable fuels.

Even if you support this level of tax on the remaining combustion cars, this is a bad version of it. It spends money on reducing emissions only through the channel of steel manufacturing. It makes carmakers buy a single product from a single set of producers to meet their environmental obligations. And it forces consumers to subsidize an inefficient part of European industry.

Because the credits are paid for by the automakers, these costs will presumably be shared across car purchases, regardless of whether they are combustion or electric.

The changes to the combustion engine ban are part of a much larger package. Besides some smaller ideas, like a new category of small cars (which would be subsidized) and changed requirements for mandatory speed limiters, the other big proposal actually tightens emissions rules.

Sixty percent of all cars and 90 percent of all vans in Europe are leased or otherwise owned by companies. The deregulatory package creates new, binding emissions targets for these vehicles.

These targets vary by country. By 2030, 90 percent of all leased vehicles in the Netherlands must be either low or zero emission, while 48 percent must be in Greece. By 2035, 95 percent of all leased vehicles in the Netherlands or Germany must be zero emission (Portugal or Poland get away with 56 percent).

I’m not sure what method was used to figure out the ‘fair’ amount of combustion cars in each country. But even if one would like to electrify the leasing industry, a tax would be much preferable to the quantity targets proposed.

The proposal also introduces a rule that would prohibit public subsidies for leased cars not made in Europe.

This protectionism is almost certain to get much worse. The French government wants the Commission to oblige automakers to source at least 75 percent of electric cars parts in Europe. In parallel, the Commission is also considering ‘Made in the EU’ requirements for the components of electric vehicles as well as other technologies like solar panels.

This proposal would create chaos in their supply chains. It would also make Europe’s cars more expensive and less competitive abroad. The sourcing requirements in particular replicate the worst parts of Trump’s tariffs, by raising the costs of the inputs into industrial processes they want to protect.

The auto omnibus is a nice example of what we have warned in a previous post: the Commission that created all the green rules would find it hard to stop creating them.

It is presumably unpleasant for leaders to unwind a project that they spent years working to create. The bureaucracy has a momentum of its own, having spent the best part of a decade thinking of all policy through this lens. Trying to impose new priorities requires a strong signal from above, a requirement that hasn’t been met by the half-hearted walk-backs of the Green New Deal we’ve seen so far.

Commission officials and supporters of the transition like to talk about learning from China. It’d be good to learn from what China is actually doing.

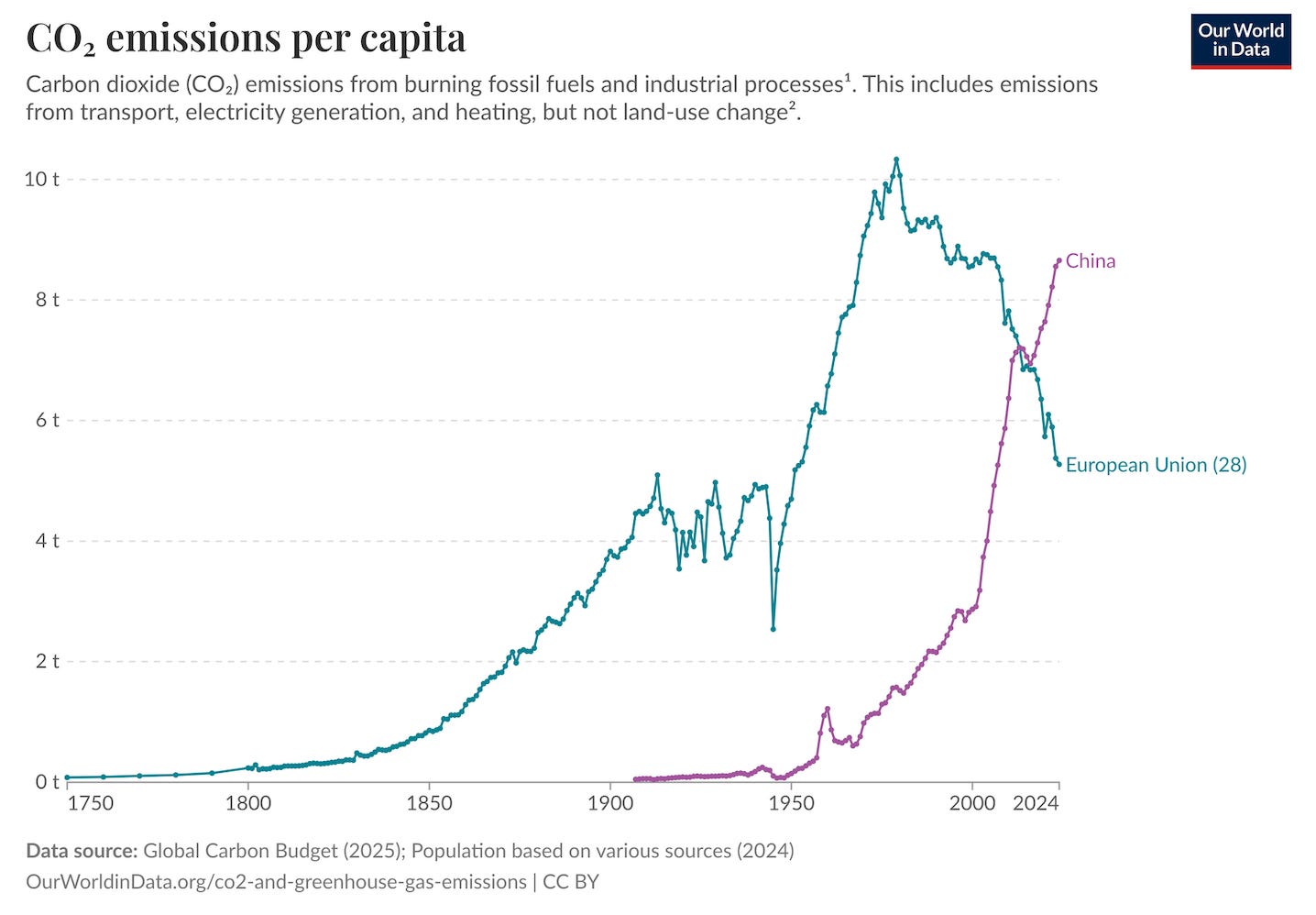

The country is building lots of renewables and nuclear power. But it is also building enormous amounts of coal, enough that its emissions per capita are now higher than Europe’s.

As Matt Yglesias pointed out, the Chinese government is not behaving as if its goal is emissions reductions. It is behaving as if it wants the ability ability to survive a blockade of oil and gas imports.

Europe continues to do the opposite of that. There are times when the energy transition and growth coincide, such as by allowing solar and building transmissions lines. But in cases where they don’t, like the car industry, growth still loses out.

What makes you think China was ever serious about emission or more broadly carbon reduction? They will do so only at a time when they feel it is in their best interests and for now more industrialization suggests nothing to change in the near term

What is the evidence for the statement that China does not have the goal of emission reduction? At least without a Twitter account, the link to Twitter leads just to a one-sentence claim. That claim seems to be based on per-capita emissions, but there is no reference to Chinese statements since the Paris Agreement or NDCs.