Should everyone get an AI industry?

Distribution and concentration

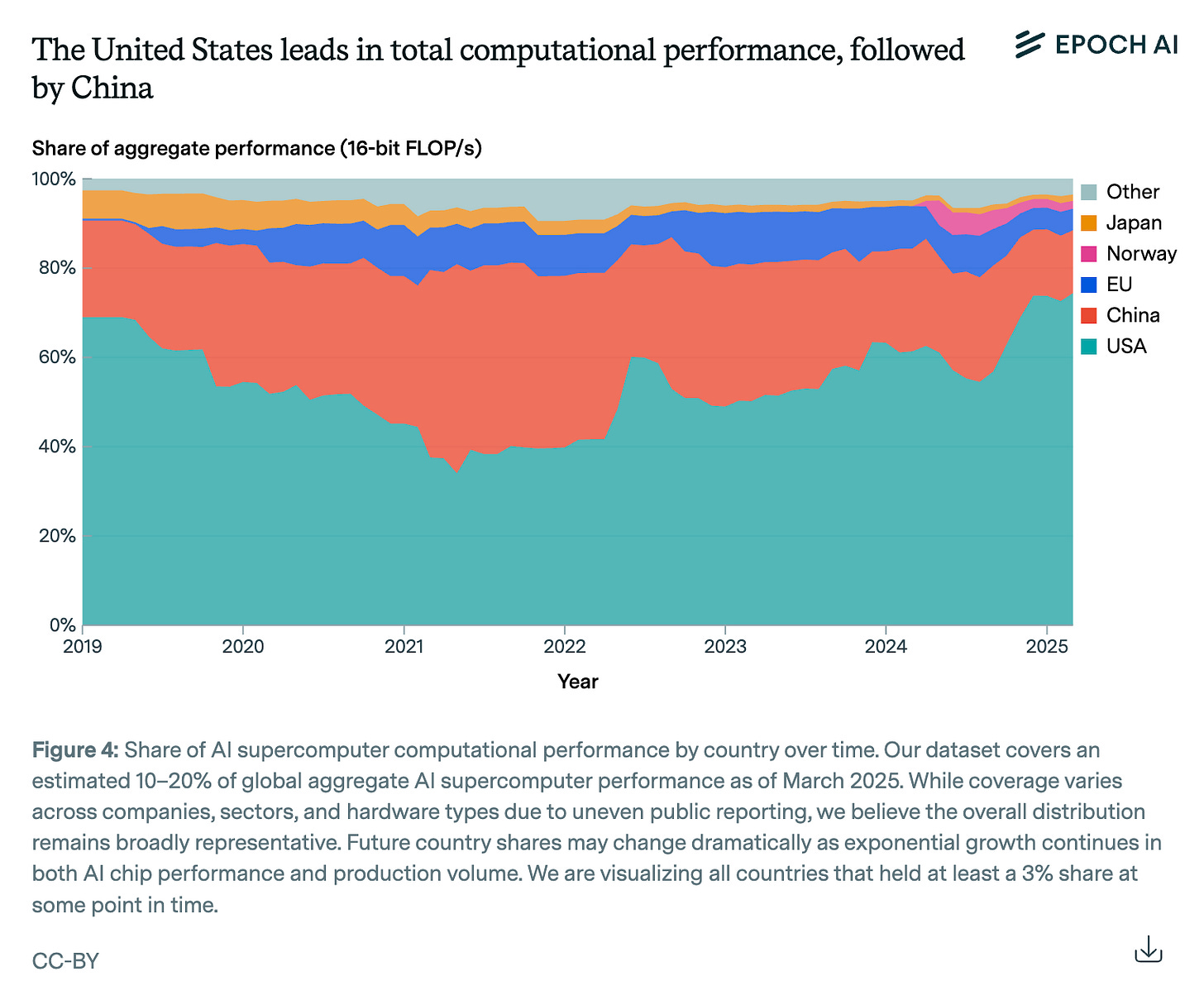

Last week, a team from Epoch AI released their breakdown of the location of the world’s largest data centers.1 Apart from the effectiveness of US export controls, the takeaway is that Europe, with just 4.8 percent of global compute, is falling behind.

But 4.8% of global compute would still allow one to operate close to the frontier, if computing power was concentrated in just a few facilities. But if you look at individual data centers, which the Epoch team helpfully lists, Europe’s deficit is even larger.

Only one European country will host a top twenty data center. France is building what would be the 11th-largest data center in the world, with 1.1 million H100s. It is also building numbers 18 through 21, all with close to 400,000 H100s each. (For a sense of scale: the current largest cluster in the world, xAI’s Colussus, has 200,000 H100s.)

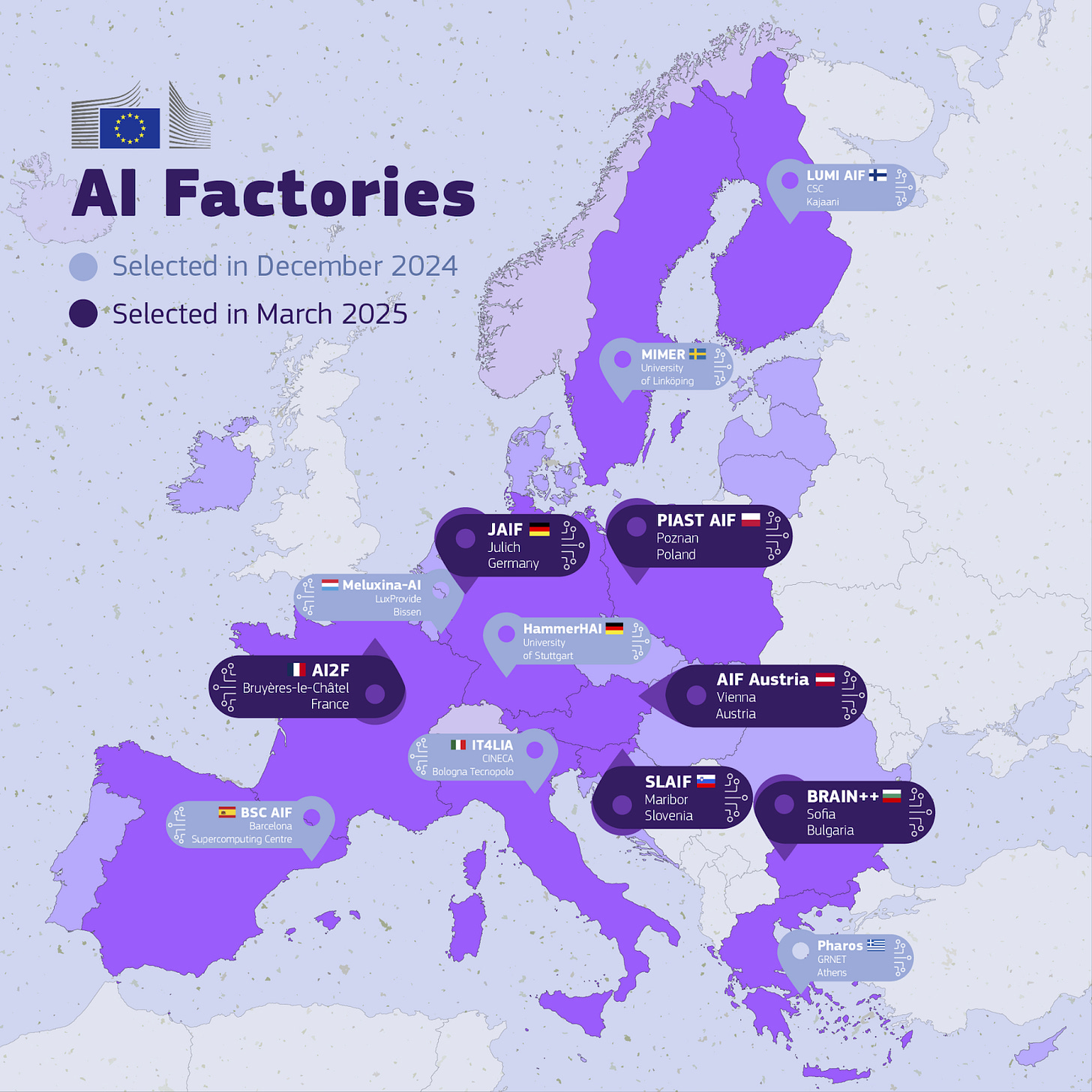

The next largest European data centers on the list are ranked 34 through 38: the European Commission’s five biggest ‘EU AI gigafactories’. Unlike in France, the bloc-owned compute represented by these clusters is spread out across the continent, and each will hold just 100,000 H100s individually.

This is surprising: due to comparative advantage and agglomeration, we’d expect data centers (and labs) to concentrate.

The fact that this isn’t happening is due to an inability to distribute the gains from concentration. This is a problem for AI, as well as every other industry with increasing returns to scale.

Cluster clustering

Data centers need certain inputs: compute, land, water, and power. These inputs are unevenly distributed across Europe. Non-household power prices range from 8 cent per kilowatt hour in Finland to 25 cents in Cyprus; some countries (like Germany with its nuclear plants) have multiple gigawatts they could bring online in the grid in months while others, like the Netherlands, find themselves so power constrained that they have banned construction of data centers that draw more than 70MW in most of the country.

Politics amplify these factors. Part of what makes France so attractive is that Macron is promising support for construction and 1 GW of nuclear power for its largest data center.

Agglomeration effects further encourage clustering, both for AI research and for compute. Areas with lots of data centers develop infrastructure, skills, and knowledge around sustaining them. Loudoun County in Virginia has more data centers than the next six US regions combined.

The same holds for the labs. Innovation involves combining ideas, so there are strong benefits from being in close proximity to other smart people with good ideas. A large majority of leading-edge AI research takes place in San Francisco and, to a much smaller degree, London.

Uneven benefits

So why aren’t we seeing this clustering in the EU? Comparative advantage would dictate concentrating data centers and labs where they are cheapest, funding them through foreign investment, and then letting the profits flow back to domestic investors.

A common argument against this is the risk that an unreliable host may choose to hold data centers hostage to renegotiate their share of the profits. A more extreme scenario involves the hosts actually taking control of the advanced AI.

But within the context of the EU we have no reason to think that true national security concerns will be at play. The real issue is the uneven distribution of revenues.

While much of the value of the AI industry flows to investors and consumers, hosting countries can charge taxes and benefit from localized spillovers. In Loudoun County, data centers now provide enough tax revenue to cover all government operating expenses. They are a true windfall: data centers pay taxes but use almost no public services. They do not use schools, and rarely need the police or local infrastructure. In fact, for every dollar Loudoun spends on services for them, it receives ten dollars back in taxes. In neighboring Prince William County, the return is even larger, 12 to 1.

But despite benefits being greatest in the areas that host them, in the US there are clear mechanisms through which concentration is still a mutually beneficial trade for other states. Federal tax receipts are automatic, and the nation is in a fiscal union. Alabama benefits from Silicon Valley's success — it would be against its own interests to try and break it up.

This is not true for the EU. While the EU’s revenues do increase as an individual country gets richer, the overall EU budget, at just over one percent of GDP, is too small to turn the concentration of an industry in one member state into a mutually beneficial exchange for most member states.

This dynamic creates misallocation everywhere. It was one of the original sins that doomed the European Institute of Technology, which was split up across different countries. A fragmented university could not be world-beating, but member states preferred a small piece of a bad university to no part of a great one. Without a fiscal union, the way to ensure a share of the pie is to physically own it.

As a result, the EU's 12 announced AI gigafactories have now been allocated to 12 different countries, some of which have Europe's most expensive power and worst permitting problems.

It is easy to attribute bad choices to ignorance about the upsides of AI or any other technology. But an inability to distribute the benefits from concentration will lead to bad allocations even if everyone involved understands how this will affect outcomes. The EIT’s problem was not that leaders underrated the global upside of an elite university, but that they correctly rated the local upside.

If AI turns out to be as important as it seems, member states might simply go their own way, as France is doing now. Land, talent, energy, and permitting are all national competences. But this means efforts will be smaller than they otherwise would be, and duplicative.

France, Europe’s leader, will have one million H100s in its largest cluster. Meanwhile, the UAE just signed a partnership with US firms to build a cluster with twenty million H100s.

While they only tracked some 20 percent of the data centers in each category, it is a representative sample that allows you to draw conclusions about the general patterns of data center deployment.

Seems like there’s an argument here for greater EU sovereignty to tap into benefits from concentration of AI data centers. Not sure if I’d want to be the politician pitching that to my constituents, but I have to imagine thats on EU policymakers’ minds.