How to build a Capital Markets Union

Europe's capital markets remain fragmented and inefficient despite decades of attempted reforms.

While European households save around 15% of their income (nearly double the 8% rate in the US), about €11 trillion—over one third of EU household savings—sits in bank deposits. At the same time, European tech startups regularly fly to Silicon Valley seeking the private equity that should, in theory, be available at home. If, instead, a Spanish start-up wants money from German pension funds and Dutch family offices, it must comply with three national rule-books. Between 2008 and 2021 almost 30 % of European “unicorns” moved their headquarters abroad (Draghi, 2024).

This disconnect is a disappointing outcome after nearly sixty years of trying to integrate Europe's capital markets. The goal was to let any saver in Europe seamlessly put their money in any European opportunity, and let companies find investors throughout the continent, whether through stocks, bonds, or loans. Yet despite multiple attempts, from the 1966 Segré Report on European financial markets, which first noted the "patchwork of duplicative and diverging rules," to the 2015 Capital Markets Union, progress remains minimal: slightly easier cross-border share listing, limited EU-wide fund sales, some retail access to some private-equity funds, a crowdfunding passport, and looser insurance-capital rules for equity.

As an ECB report recently put it “the progress made in developing and integrating the capital markets has been limited, impacted by the insufficient advancement of the most ambitious reforms needed to transform capital markets.”

The result is an overdependence on banks, which typically favor established companies with existing relationships and assets to pledge rather than innovative startups. Young, risky ventures need equity financing—money invested for ownership rather than requiring fixed repayments—but Europe's fragmented and inefficient system makes this difficult to secure domestically.

The Commission's newly released Savings and Investments Union proposal (March 2025) continues this pattern of slow, incremental change. It makes proposals such as EU “Savings and Investment Accounts” with possible tax relief, financial-literacy drives, automatic pension enrolment, simpler listings, more securitisation, less “gold-plating” (extra national rules added to EU directives) and easier withholding-tax refunds. It also proposes to increase the European Securities and Markets Authority’s (ESMA) powers, yet still leaves twenty-seven supervisors in place–contrary to the suggestion in Mario Draghi’s report that a single EU regulator was needed.

In sum, beneath the rhetoric, the new plan offers more slow harmonisation while preserving the banks central role. The only measure with bite is wider loan securitisation, which frees bank balance-sheets but does little for equity funding. The likely outcome is even deeper “bancarisation” of our economies: more finance will flow through banks.

The banking stranglehold–and why member states protect it

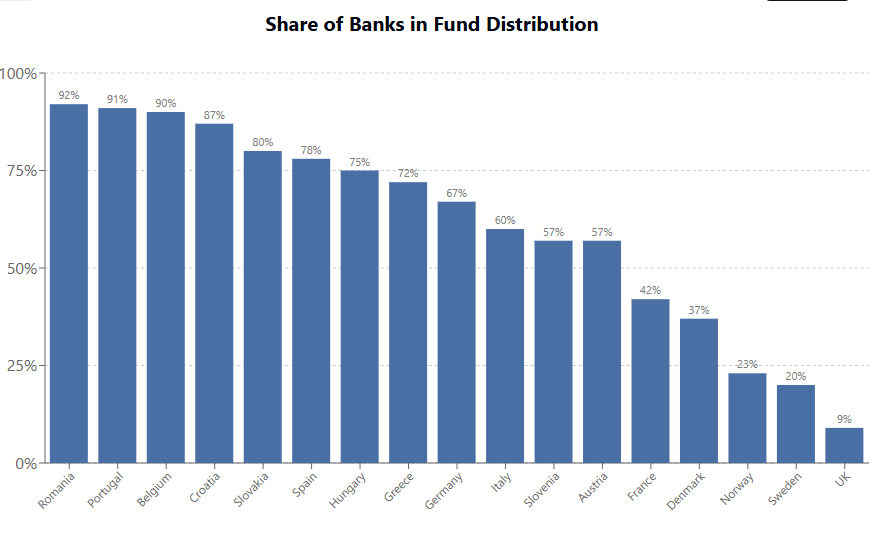

In Europe, whether savers want a plain vanilla deposit account, an equity fund or a bond, they usually obtain it through banks. Banks control about 45 % of retail fund assets and often sit behind the broker or adviser that sells the product. In Romania or Portugal, “captive” bank channels distribute 92 % of funds. Spain’s figure is 78 %; Germany and Italy’s are similar.

Banks own the shelfspace and charge for access to it. Fund providers pay for placement; the biggest kickbacks secure the best spots, so banks push their own high-fee products while low-cost index funds stay out of view. Rules sold as investor protection force retail clients to buy through intermediaries, and tax wrappers such as French assurance-vie or Germany’s Riester pensions lock cash inside bank-linked vehicles. National lobbies—GBIC in Berlin, Fédération bancaire française, ABI in Rome—then block reforms such as the hand-over of supervision to ESMA.1 Even consumer groups, demanding ever tighter protection, unintentionally reinforce the same channels.

Because households reach markets only through bank wrappers, any reform that threatens commissions or national supervision cuts straight into a core profit engine.

The question is why the states protect this monopolistic power of the banks. The answer was not obvious at all to me before being in the European Parliament, and I will return to it more carefully next week when I discuss the death of European deposit insurance. But the basic idea is that banks’ political weight extends beyond plain lobbying. Finance ministers like having large and powerful domestic banks they can pressure in a crisis. National governments therefore defend their banks in ECOFIN and the Council. Each Capital Markets Union package sounds ambitious on day one, but then the clauses that would loosen the bank grip slowly disappear.

A successful reform must accomplish two seemingly impossible aims. First, increase the share of credit that flows directly from savers to companies through equity, private equity or debt. Second, integrate the fragmented national markets. Both of those objectives directly conflict with the interest of the winners in the current system: the banks.

Lessons from abroad

The United States once had its own balkanised private equity market. Before 1996 a company raising private capital had to clear “blue sky” laws in every state:

To illustrate, if a startup headquartered in Seattle issued shares to investors located in Washington, California, New York, and Texas, the startup needed to comply with the blue sky laws of these four states. Importantly, it was the issuer—that is, in this example, the startup, not its investors—that needed to comply with each state’s blue sky law. (Ewens and Farre-Mensa, 2020)

Congress did not harmonise these fifty regimes. Instead, the National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 1996 (NSMIA) gave federally defined private offerings automatic exemption from state law. The resuls were large and fast, according to Ewens and Farre-Mensa (2020): late-stage firms became four times likelier to draw out-of-state investors; average round size rose 30 %. The market grew from $1.3 bn in 1995 to $33 bn in 2015.

NSMIA succeeded because it embraced a completely different philosophy. Rather than harmonizing diverse regulations, it created a clear path that bypassed them.

Europe needs its own version of NSMIA—not more harmonization, but a simple bypass route. The idea of a “28th regime”—an optional, EU-wide code of corporate, securities and insolvency law that firms could adopt instead of navigating 27 national rulebooks—has gained powerful supporters. Enrico Letta champions it in his April 2024 single-market report. Mario Draghi's report urges the same device.

An optional regime would avoid many political-economy roadblocks. National supervisors would keep control of domestic offers; banks could still sell their own products. The 28th regime would not abolish the existing order; it would create an escape from it. The dual system might worry large states that fear losing power, and incumbents would still lobby, but the US experience shows it can work.

In sum, the Commission's strategy offers ambitious rhetoric but will likely end up only making bank intermediation more efficient rather than creating genuine alternatives. If Europe is serious about mobilizing its vast savings for productive investment and keeping its entrepreneurs at home, the 28th regime offers the most realistic path forward. The question is whether European leaders have the political will to implement Letta's and Draghi's vision and challenge their own financial establishments with genuine competition in capital allocation. Sixty years of failed harmonization suggests it's time to try.

References:

Arampatzi, Alexia-Styliani, Rebecca Christie, Johanne Evrard, Laura Parisi, Clément Rouveyrol, and Fons van Overbeek. "Capital Markets Union: A Deep Dive-Five Measures to Foster a Single Market for Capital." ECB Occasional Paper 2025/369 (2025).

Draghi, Mario. "The Future of European Competitiveness Part A: A competitiveness strategy for Europe." (2024).

Ewens, Michael, and Joan Farre-Mensa. "The deregulation of the private equity markets and the decline in IPOs." The Review of Financial Studies 33, no. 12 (2020): 5463-5509.

A tax wrapper is a legal shell that grants tax relief only while assets stay inside, so investors cannot move money without losing the break. In France, assurance-vie contracts defer tax on gains and let savers withdraw the first €4 600 (€9 200 for a couple) each year tax-free after eight years; the selling bank or insurer controls the fund list and collects retrocessions, so low-cost index funds almost never appear. Germany’s Riester pension gives tax deductions and state bonuses on up to €2 100 of yearly contributions, but savers must use certified contracts that guarantee paid-in capital; banks and insurers design these contracts, load them with fees, and make transfers hard, so assets stay captive. Because wrappers tie customers to distributors, banks sell shelf space to fund houses: high-fee products buy the best spots, cheap funds stay hidden.

Great article. One dimension worth adding is the unintended consequence of recent anti-money laundering regulations. While introduced under the banner of financial integrity, AML rules have further strengthened banks' gatekeeping role, especially in retail and cross-border finance. This has made it harder for fintechs and other non-bank actors to compete, deepening the very dependence on banks that the Capital Markets Union aims to reduce. Might be an interesting next topic.

Thank you for this clear article. It seems like similar to the Single Market (as in your post last week), Member States themselves erect most of the barriers. While at the same time quite hypocritically calling on the EU to remove barriers and 'deepen' the Single Market/Capital Market. Also came across this article just before on this https://www.politico.eu/article/brussels-belgium-europe-single-market-china-european-union-regulations/