Why is the AI Act so hard to kill?

Some insight into how the sausage is made

“[Citizens] are disappointed by how slowly the EU moves. They see us failing to match the speed of change elsewhere. They are ready to act—but fear governments have not grasped the gravity of the moment.” Mario Draghi, 16.09.2025.

“Under the influence of alarmism and time pressure solid laws are not created” Gabriele Mazzini, principal author of AI Act Draft, Interview with Neue Zürcher Zeitung 12.09.2025

I spent the last two weeks in Hong Kong and Palo Alto (my summaries for one and the other) at artificial intelligence conferences. Many in both places believe AI will be the largest technological change humanity will experience since the Industrial Revolution. Education adapts continuously to what children learn and understand. Science labs are automated, which massively accelerates discoveries. Self-driving cars are a reality beyond San Francisco, cutting the risk of accidents, death and injuries by 91%.

In such a world, Europe faces a problem: the AI Act, together with the General Data Protection Regulation, will lead the continent to miss this transformation.

The problem with the AI Act

In one of our first pieces on this blog we covered the AI Act and all the complications it poses. Consider one concrete example: education, one of the most promising use cases of AI.

Instead of teaching all kids the same materials, why not continuously tailor the lessons to what they don’t know, focus on the concepts each kid struggles with, and skip what they already understand? An American entrepreneur building exactly this tool told me in Palo Alto he would not enter the European market because such a model would soon be illegal in Europe.

Why? The AI Act treats his product as high‑risk, since it evaluates learning outcomes and directs learning in educational settings (Annex III). High‑risk systems must undergo conformity assessments and meet strict duties: risk‑management systems (Art. 9), robust data governance and logging (Arts. 10 and 12), information obligations for users and deployers (Art. 13), and effective human oversight (Art. 14). One key feature is banned: using AI to infer students’ emotions and adapt to their frustrations (Art. 5(1)(f)).

GDPR demands “purpose limitation and data minimization,” so “collect everything” telemetry is hard to justify (Art. 5(1)(b)–(c)). People have a right not to be subject to decisions based solely on automated processing that significantly affect them (Art. 22), and Recital 71 adds that such measures should not concern a child—so a fully automated path needs human review at each step.

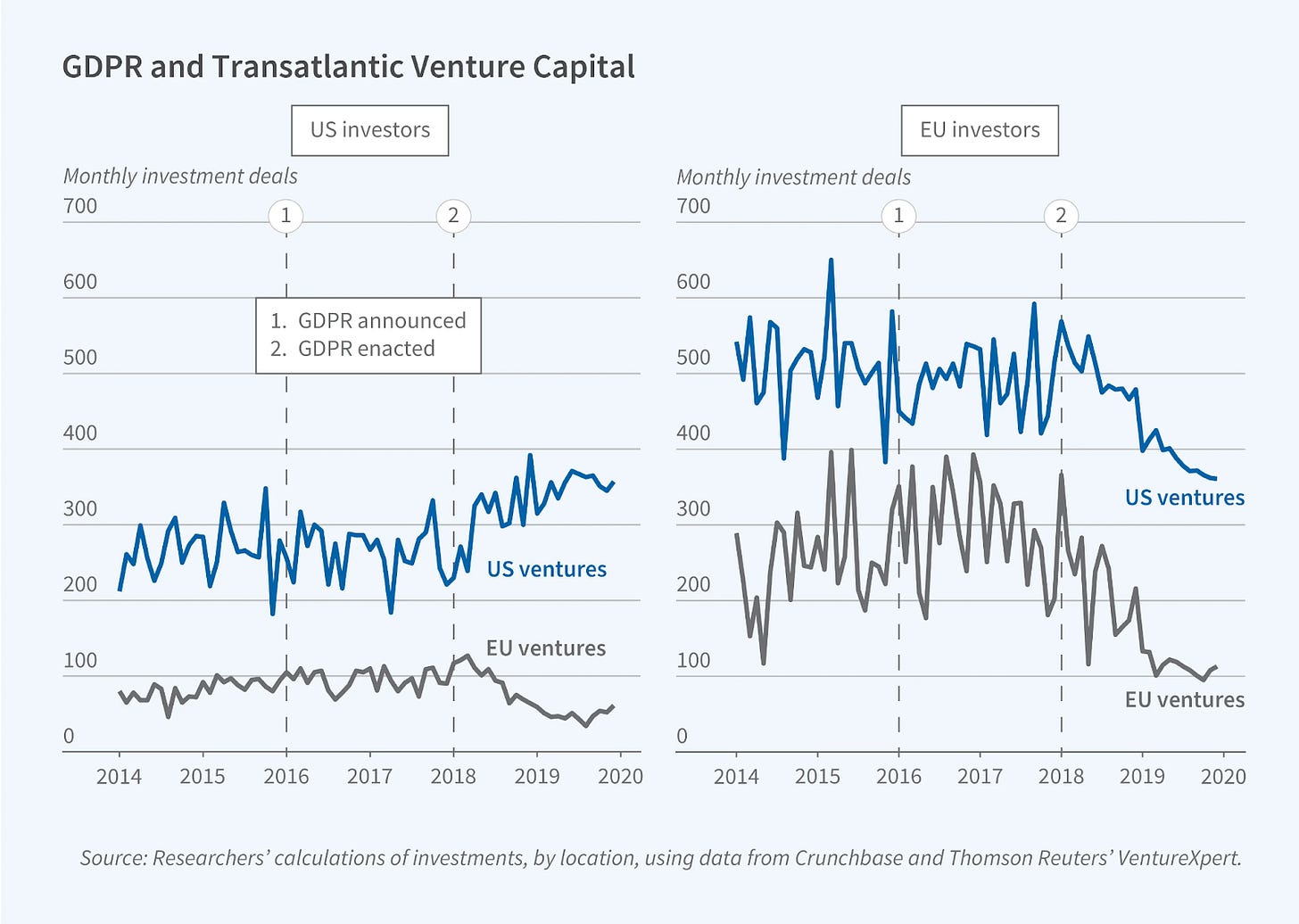

Indeed, the Draghi report called for deep reform of digital legislation, and in a recent speech, Mario Draghi called for a suspension on implementing the AI act high-risk categories.1 He also criticized GDPR, noting it has increased by 20% the data costs for EU businesses relative to American ones. Recent research, summarized in the chart below, shows detrimental effects of this piece of legislation for startup funding.

But one year after the Draghi report, Europe has done nothing to correct these errors. The Commission’s approach to implementing the Draghi reforms has been to introduce a set of “Omnibus” simplification bills. These bills reduce reporting duties, raise reporting thresholds, and extend deadlines. But they do not reopen the substance of the Green Deal, digital legislation, or Europe’s Single Market fragmentation.

In the digital area, the Commission has opened a call for evidence to collect research and best practices on how to simplify its legislation in the upcoming Digital Omnibus, especially when it comes to GDPR changes (cookie consents in particular may be changing). But overall, no sense of urgency appears evident in the AI Act, even though parts of the act are already being implemented, and the main high-risk provisions Draghi wants to pause come into force in August 2026.

Meanwhile, the gap in AI development grows. Last year, U.S. companies produced 40 large foundation models, China produced 15 and the EU produced just three. The AI Act, rather than closing this gap, appears designed to widen it.

Why is the act so bad?

One reason the act has problems is its timing. Gabriele Mazzini, the AI Act’s principal drafter inside the Commission, recently gave an interview with the Zurich newspaper NZZ, where he blames the timing of ChatGPT for part of the mess.

The first Commission draft of the Act was published in April 2021, and the EU institutions had been slowly developing their positions. When ChatGPT appeared, the Council of Ministers was one week from finalizing its own draft.

The seemingly sudden appearance of general-purpose AI created “enormous time pressure” and fueled “apocalyptic scenarios.” A letter from the Future of Life Institute, signed among other luminaries by Elon Musk, called for a six-month pause on AI development. In 2023, Commission President von der Leyen warned in her State of the Union speech about AI potentially extinguishing humanity.

Instead of starting a careful, separate process, lawmakers wanted to act immediately. They bolted a new section on general-purpose AI models onto the nearly-finished legislation. They also failed to adapt the existing model—particularly the risk-based categories—conceived for a world without GenAI. With the Commission and Parliament mandates expiring in Spring 2024, “everyone was keen to pass a law fast, to say: ‘We are regulating this for you.’”

The current mess

This explains the chaotic coverage of general purpose models, which is hundreds of pages of guidelines, codes, and templates on the way, none of which bind and all of which add ambiguity.

But many of the other poor provisions in the AI Act cannot be explained this way. The high risk categories, including the governance of education models from the example above, predate the general purpose rush. So does the byzantine system that is meant to lead to ‘harmonization’: an EU AI Office, a board with member state representatives, a scientific panel, and an advisory forum at the European level, along with actual enforcement by 27 different Market Surveillance Authorities (one per member state, sometimes more in federal countries like Germany), plus Notifying Authorities supervising conformity assessment bodies.2

Nor does a rush due to ChatGPT justify the requirement that every authority have an “in-depth understanding of AI technologies, data and computing, personal data protection, cybersecurity, fundamental rights, health and safety risks.” EU bureaucrats already report difficulties staffing AI offices at the European level. Finding qualified experts for the Market Surveillance Authority in every small European region is even harder.

The Brussels regulatory machine

Why did we not get our act together? And why, on the edge of the precipice, is there no push to fix it now? The cause of and lack of action to reverse these legislative mistakes is due to a deeper problem in the way Brussels works.

The Commission and Parliament have little fiscal power—the EU budget is 1% of EU GNI, and the Union lacks direct tax authority. When you cannot spend at scale, you legislate.

This creates a regulatory machine whose guaranteed output is more regulation. Think about how the incentives work: You’re a Director-General at the European Commission where the Treaties give you limited power and you have no significant budget–say, for instance, housing. What’s your path to success? How do you ensure a promotion to Director General of Competition or Trade, where the Commission has real power? You pass a regulation or directive. The Commission has the exclusive right of initiative. You’ll find eager MEPs happy to work with you—it’s their job to legislate and housing sounds great. The Council will agree too; they want to do something, without fighting entrenched interests back home.

This creates a structural bias toward new rules. There’s also political lock-in. Asking the authors of complex laws—legislators and civil servants who fought over every comma—to dismantle their work means asking them to admit error.

Where we stand

Europe has a window to act. High-risk provisions don’t apply until August 2026. Mazzini, the author, wants to revisit it entirely: “stop it and undo what already applies—or change it substantially... As for the law, I now have doubts about whether AI technology should be regulated at all. It would have been better to close specific legal gaps rather than betting on one big throw.”

But incentives point the other way. The Commission which rushed this law won’t admit error. Member states lack the unity to demand fundamental change. The regulatory machine has no mechanism to encourage self-correction, even though the law has built in provisions that allow the Commission to suspend large parts of it (by reclassifying items away from high or systemic risk).

Europe stands at the edge of an AI revolution. We have talent, research, and market size to compete. The AI Act is a monument to a broken system that prioritizes regulatory activity over economic vitality. But until Europe addresses the structural incentives that led to the act—the bias toward legislation over investment, the lock-in effects of legislation, the fragmentation that prevents scale—it will continue to regulate itself into irrelevance while others build the future.

“But the next phase, which concerns high-risk AI systems in sectors such as critical infrastructure and healthcare, must be proportionate and support innovation and development. In my opinion, implementation of this phase should be suspended until we better understand its drawbacks. More generally, implementation should be based on ex post evaluation, judging models based on their real-world capabilities and demonstrated risks.”

On reading the draft, a lawyer friend remarked that this proliferation of national authorities may paradoxically allow some countries to maintain an AI-friendly culture in their countries, by basically neutering the authorities. The claim remains to be seen; the fragmentation is undeniable.

Have to say that EU officials are almost obsessed with regulating everything. Banking, online speech, cookies, charging ports for electronics, and now AI.

The EU is systemically set up that way, and not sure if anything other than abandoning it all together can change it.

I wonder if artificial intelligence itself, trained not only with specific historical data (regulatory items vs. open developments) but also open to creative exploration of the future, could help us establish an efficient compromise between regulation and investment in this field of AI development. Could such a process of questioning AI be fed with charts like the one on "GDPR and Transatlantic Venture Capital," but extended to capture the most sensitive pieces of GDPR vs. specific AI ventures?