The trouble with wind

It's a poor choice for the future

In a few days, the Netherlands will have a new government, consisting of the social liberals (D66), the market liberals (VVD), and the Christian democrats (CDA). The coalition wants to make it easier to build housing, increase spending on defense, decrease spending on pensions (relative to the baseline), loosen labor law, and found a Dutch ARPA. In many ways, the coalition can be thought of as an effort to improve the circumstances of the country’s young and future inhabitants at the expense of the old and middle-aged. The health care deductible is increasing and so is spending on education.

This makes it disappointing that the coalition’s big energy plan is to build 40 gigawatts of wind capacity financed by contracts for difference.

The North Sea is as good a place for offshore wind as exists anywhere. Most of it is only 15–30 meters deep, and wind speeds average over 10 meters per second. The surrounding countries are some of the most densely populated in the world (England, with 450 people per square kilometer, is not quite as dense as the Netherlands, with 541), and have some of the cloudiest weather, which makes them less suitable for solar.

But the economics of wind are quite poor, and the nature of contracts for difference means that the high costs of wind power now will lock in high electricity prices for years to come.

Optimistic predictions had the levelized cost per megawatt-hour of offshore wind down to $40 by 2030, decreasing much like solar has. Unfortunately, this hasn’t happened. The National Renewable Energy Lab in the US does good annual analyses of the cost of offshore wind. In the most recent one, it costs over $110 per megawatt-hour, and the price has increased in recent years.

The cost of solar has decreased so much because a lot of the cost is manufacturing the cell. This isn’t the case for offshore wind. The turbine is just 24 percent of the lifetime cost, and a significant chunk of that goes to raw materials. 35 percent of the cost is support infrastructure, including the foundations, undersea cables, substations, and installation, and 27 percent goes to operations and maintenance after installation. Even if the turbine gets more efficient it won’t help much, as more efficient turbines are often larger and so more expensive to install.

Rising costs have caused trouble for wind manufacturers. Ørsted, the world’s largest developer of offshore wind, has lost 88 percent of its value over the last five years, including 76 percent before Trump took office. Vestas, which makes turbines, has lost 36 percent of its value over the last five years.

Despite the political excitement, few offshore developers are that enthusiastic about North Sea wind anymore. In October last year, the Netherlands ran a one gigawatt tender for offshore wind in the North Sea and received no applications at all.

Part of the reason for that failure, I imagine, was that 42 percent of the points in the application were granted for contributions to sustainability and the ecosystem: you could get more points for minimizing porpoise disturbance days (26) than you did for proving that you, the foundation manufacturer, the foundation installer, the wind turbine manufacturer, the wind turbine installer, the cabling manufacturer, and the cabling installer each had done this more than fifty times before (22). Also, only one kind of foundation (a monopile) was permitted by the Environmental Impact Assessment.

The other reason was that the tender was unsubsidized, and developers are unwilling to back North Sea wind turbines without significant public monies attached.

Contracts for difference

To subsidize wind developers, North Sea countries – first Britain and now the Netherlands – have turned to the contract for difference (CfD). The CfD first became common in the financial world in the 1990s, as a way for hedge funds to get exposure to price movements without owning the underlying asset.

In the CfD, two parties agree to a strike price for a good along with a settlement period. If the market price in the settlement period is below the agreed price, the purchaser of the CfD pays the difference between the market price and strike price to the seller. In a two-sided contract, the same happens, but the seller also pays the difference to the purchaser if the market price of the goods exceeds the strike price.

The CfD in the energy world is usually two-sided. The government promises to pay the producer of the electricity the strike price minus the market price over the next 12 to 20 years, depending on the country. This guarantees that the seller will always receive the same amount for the power, no matter what happens elsewhere in the market.

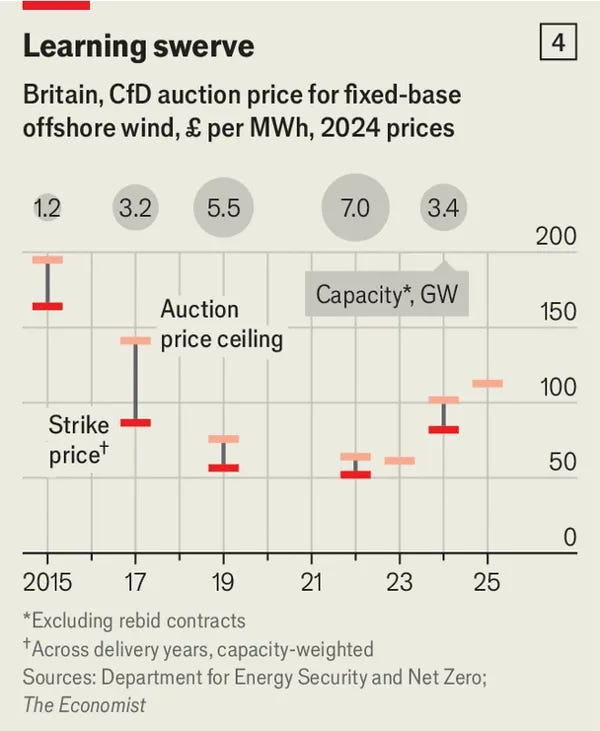

In the best case scenario, CfDs create certainty and lock in favorable prices for consumers. In 2022, Britain sold seven gigawatts for under 50 pounds per megawatt-hour – a good deal for the government.

But if the price of the underlying good is high at the time of auction – in this case power generation with wind turbines – the CfD just locks in high prices.

In 2023, developers refused to bid on Britain’s CfD auction, even after the maximum price was raised. To keep building wind capacity, the government raised prices in 2024, and even further in 2025.

In the most recent round, the British government offered £91 per megawatt-hour for 8.25 gigawatts, locked in until the late 2040s. That price is above the price of generating electricity with gas today, despite gas being extremely expensive compared to historic levels. The recent auction guarantees that Britain will have some of the most expensive energy in the world for the next two decades.

This will be the Netherlands’ problem if the coalition’s plans proceed. As a trial, the government just announced a one-sided CfD for one gigawatt for up to €104 per megawatt-hour. The price of generating electricity in the Netherlands is only roughly a third of the price faced by consumers, so at the maximum price this trial will buy electricity a few percent more expensive than what we have today, for the next 15 years.

There are other issues with wind beyond its costs. The number of prime sites is limited; as those get taken, the costs of installation increase and the returns decrease. And there is the problem of intermittency: when the wind doesn’t blow, power doesn’t get generated.

But these problems will probably get solved. The learning curve for wind is not as steep as for solar but still negative; installation technology and more efficient turbines will make worse sites viable; batteries, nuclear, and transmission will help alleviate the problems with intermittency.

But CfDs mean that the prices for the next decades are the ones we face today, not the ones we may face in the future. The Netherlands has an installed electricity generating capacity of 63 gigawatts. The proposed 40 gigawatts will add two thirds to that.

The Netherlands’ plans with wind are extreme, but representative of a larger group of North Sea countries. The first wind turbines that generated more than a megawatt were built in Denmark in 1978. Along with the Netherlands, Britain, and Denmark, Germany and Ireland all want to hit their climate goals primarily with wind power.

I feel bad spending as much time as I do on this blog criticizing Europe’s climate efforts. But the scale of the resources being allocated, the degree to which Europe is alone in this effort, and the role of expensive energy in Europe’s productivity difficulties make getting this right hugely important.

The exciting thing about the new Dutch government is that it understands zero-sum transfers are taking place between generations, and it has decided to rebalance them towards the young. Making the choice to lock in high electricity prices for decades to appease climate-conscious voters today would do the opposite of that.

I think problem in wind energy is the same as in nuclear energy. Most cost reductions are from vertical scaling (i.e. bigger blades). Just like in nuclear you will go on with vertical scaling up untill the point logistics get so massively complicated that it gets close to unbuildable. We are hitting the S-curve on vertical scaling (especially on land). I would say: one advantage of offshore wind is that you can keep on vertically scaling for longer, due to logistics (you can't transport truly MASSIVE blades on land, but you can over sea). Also: interest rates arent that low anymore – that's a major source of cost. https://decorrespondent.nl/15355/kernenergie-niet-nodig-niet-slim-en-niet-te-betalen/a95a368a-57e8-0a02-3771-a37846ed2fba This is quite different from solar energy.

Some more notes: Netherlands is also paying for the connection to the grid (which is different in UK I think?). This is quite expensive for offshore infrastructure. It's also a bit of a mess, because the users of Dutch wind energy are also foreign, while grid cost are payed by domestic users.

Dutch power prices are extremely low during large part of the summer due to massive solar roof expansion. It's quite difficult to make money for wind developers with low or negative prices during much of the summer. Wind is negatively correlated with solar energy (more in winter than in summer), so the business case might improve if heating demand gets electrified.

I think we should be bullish on solar energy, but the fact is that the Northern-Europeean countries without hydro are not very well suited to the cheapest technologies with most energy demand in the winter. Countries like Spain or states like Texas are.

I don't see the alternative to Wind for Europe. Overbuilding solar to such a degree that you still produce enough energy in the Winter is completely unrealistic any time soon, and battery storage doesn't store energy long enough to use excess generation from the summer in the winter. Coal and Nuclear energy work as a base load but become way too expensive if you are turning them off for most of the year due to high solar generation, there isn't a lot of untapped potential for Hydropower, and we want to reduce our dependency on imported fossil fuels, because we would be dependent on at least one of Russia, the US and the Gulf, and all of them are at best unreliable allies that are willing to coerce us with this dependence and at worst actively hostile to us.

Wind energy is relatively complimentary to solar and I don't see any alternative for Europe for electricity generation in the winter that doesn't have worse problems.