The Constitution of Innovation

A New European Renaissance

By Luis Garicano, Bengt Holmström & Nicolas Petit

(You must have wondered what I was up to— well this!: We have been working very hard to make a manifesto with concrete suggestions on what Europe should change to benefit from its enormous scale and unleash a new renaissance. Here is now the entire manifesto- also available in a dedicated micro-website, go there for the footnotes. Reactions, comments and thoughts as well as social media comments very welcome)

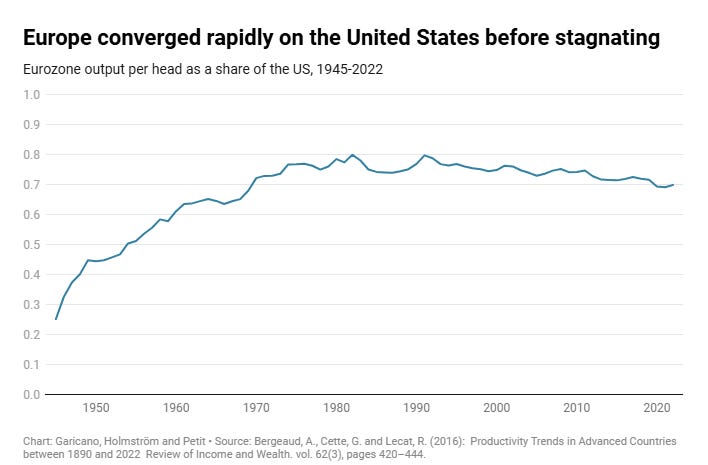

In 1945, Europe was ruined. Average incomes were 22 percent lower than the United States at the start of the war; by the end that gap had grown to 75 percent. These economies were different in kind, too. In 1950, for every farmer in America there were 2.7 manufacturing workers, compared to just 1.3 in Germany and 0.92 in France. 1

But rather than stay poorer, as one might have expected, Europe rapidly rebuilt itself. Not just did it reach its previous levels of development within nine years, it then blew past them. Even though the decades after the war saw some of the fastest growth in American history, Europe grew much faster. In thirty years after 1950, the core European economies grew so fast that consumption per capita tripled while their citizens worked 400 fewer hours per year.2

Part of this growth was catch-up: converging on the frontier America had set for us. But part of it was pushing the technology frontier forward. By the end of the 1970s, Europe was mass-producing jet engines and nuclear power plants. This success was not an accident; it was ‘constituted’ through a set of common beliefs, proved principles, and appropriate practices that stimulated innovation.33. As in Friedrich Hayek’s 1960 book, The Constitution of Liberty, we use ‘constitution’ to mean the basic principles and practices needed for innovation and prosperity to return to Europe, not a legal document.

However around 1980, this unprecedented growth period ended. While the United States maintained a remarkably constant 2 percent growth rate in average income, the European core economies decelerated, slowly and then sharply. Since 1995, Europe’s average annual growth has been just 1.1 percent; since 2004, it has been a mere 0.7 percent – all while the United States has continued on its steady track. By 2022 the relative gap in output per head has returned to where it was in 1970. Decades of convergence were surprisingly wiped out.4

A long list of reports by European luminaries have diagnosed this decline. The 1988 Cecchini Report calculated the enormous ‘cost of non-Europe’; the 2004 Sapir Report identified Europe’s ‘disappointing’ growth; and the contemporaneous Kok Report argued the EU was failing through lack of political will. In 2010, Mario Monti warned that the internal market was suffering from ‘integration fatigue.’ Last year, Enrico Letta found the European market critically fragmented, while Mario Draghi concluded that Europe’s competitiveness had fallen so far it now required ‘radical change’ just to survive.

Despite these warnings, the European Union’s response to its decline has been weak where it needs to be strong, and active in the areas where it should be passive. The problem is not a lack of reports, but a system that refuses to prioritise.

The continent faces two options. By the middle of this century, it could follow the path of Argentina: its enormous prosperity a distant memory; its welfare states bankrupt and its pensions unpayable; its politics stuck between extremes that mortgage the future to save themselves in the present; and its brightest gone for opportunities elsewhere. In fact, it would have an even worse hand than Argentina, as it has enemies keen to carve it up by force and a population that would be older than Argentina’s is today.

Or it could return to the dynamics of the trente glorieuses. Rather than aspire to be a museum-cum-retirement home, happy to leave the technological frontier to other countries, Europe could be the engine of a new industrial revolution. Europe was at the cutting edge of innovation in the lifetime of most Europeans alive today. It could again be a continent of builders, traders and inventors who seek opportunity in the world’s second largest market.

The European Union does not need a new treaty or powers. It just needs a single-minded focus on one goal: economic prosperity. This prosperity is necessary for its own sake and for all the other things we want Europe to be: a bulwark against Russian tyranny, a generous supporter in lifting the world out of poverty, and a champion against climate change.5

As Jean-Jacques Servan Schreiber observed in the 1960s:

The degree of autonomy, prosperity, and social justice that a country aspires to depends upon its growth rate. A society enjoying rapid growth is free to define its own form of civilization because it can establish its order of priorities. A stagnant society cannot really exercise the right of self-determination.

To achieve this prosperity, we need to return the Union back to its original intent, as a federal body dedicated to economic development through a common and free market.

The neglect of that purpose has been overwhelming. The European Union currently pursues a long list of goals, including (as given by the Commissioner titles): promoting the ‘European way of life,’ ‘health and animal welfare’, ‘environment, water resilience and a competitive circular economy’, ‘intergenerational fairness, youth, culture and sport’ or ‘social rights and skills, quality jobs and preparedness’. Meanwhile, the internal market has become so fragmented that, according to recent IMF analysis, internal trade barriers are equivalent to a 44 percent tariff on goods and 110 percent on services. And, as Mario Draghi famously pointed out, no European company worth over €100 billion was set up from scratch in the last 50 years; the continent that birthed the industrial revolution has wrecked its own ability to catch the digital one.

These are not accidents of history; they are consequences of our choices. In recent decades, the Union and its Member States have confused regulation with progress and bureaucracy with integration.

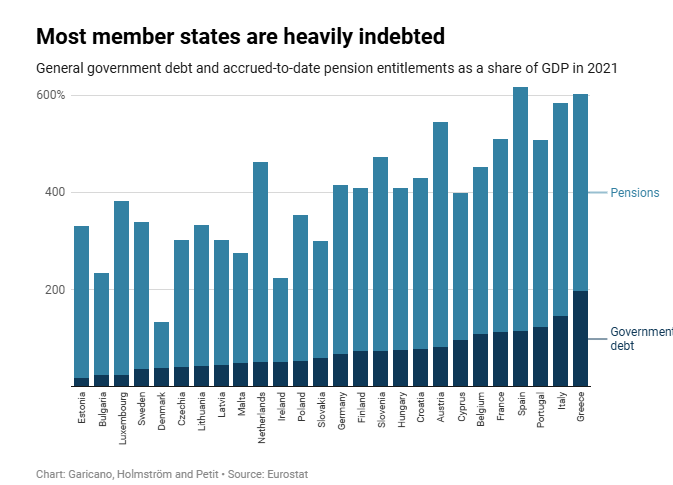

If the European Union keeps stagnating, our countries will not be able to maintain the things its citizens take for granted: unemployment benefits, free healthcare, lifelong pensions, and affordable education. Growth is necessary to pay for existing commitments, and fulfill the recent deluge of new ones. Stagnation is going to make the European welfare state a utopia of the past.

This paper proposes a different path, one guided by pragmatism, not ideology. This requires a clear set of principles to focus the actions of the European Union on a few critical objectives and act decisively to achieve them. To understand how to correct its course, we must first examine how the EU lost its way.

How we lost our way

The European project began with a clear purpose. The 1950 Schuman Declaration proposed integrating the coal and steel industries – the raw inputs of war – to make conflict between France and Germany ‘not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible.’ This approach, known as functional integration, was based on the proposition that when economies become interdependent through trade, war becomes prohibitively expensive.6

The Coal and Steel Community (1951) evolved into the Economic Community (1957), creating the world’s largest trading bloc. The Single Market (1993) removed trade barriers between Member States. The Euro (1999) provided price stability across borders. Nations that shared a long history of violence were progressing towards what Robert Kagan called a ‘post-historical paradise of peace and relative prosperity’.7

But initial success led to mission creep. With peace secured, the European institutions began to look for new problems to solve. Jacques Delors, Commission President, captured Europe’s principle of action in a famous metaphor: ‘Europe is like a bicycle. It has to move forward. If it stops, it will fall over’. This mantra — that integration must constantly increase or founder — converted the European peace project into a self-perpetuating regulatory flywheel. Legal scholars, practitioners, and policymakers transformed an untested vision into a grand narrative, ‘integration through law’.8

From the 1980s Europe began legislating on topics with little to no connection to economic integration or peace – the amount of fruit in marmalade, the conditions under which a piece of clothing could be considered sustainable, or what constitutes appropriate political advertisement. What started as functional integration – removing barriers to trade – morphed into the superstition of regulation for the sake of integration. Each new regulatory text justified the next, creating a governance culture where ‘more Europe’ became the answer to every question, regardless of whether European intervention added value.

This regulatory overkill has culminated with the response to the digital and environmental challenge, which led to an avalanche of rules driven by the ‘Brussels effect’— the theory that pretends that writing legal rules sets global standards and thus gives European firms a competitive edge.9

In practice, the Brussels effect has created high costs that harm European firms more than their global rivals. For example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), favors US tech giants which can shoulder the burden of massive compliance costs but undermines European startups. A recent study shows that GDPR reduced European Union technology venture investment by 26 percent relative to the US.10 The AI Act follows the same logic, imposing technical requirements for market access on an emerging technology before Europe has even created one major AI company.

These rules raise the cost of innovation and slow the dissemination of digital technology across the European Union. The regulatory bicycle is pedaling at full speed. But it is pedaling towards a wall of bureaucracy created by its own policies.

Economic foundations

Europe must do less, but do it better. Prosperity through economic integration should again be central to the Union. In practice this will mean two things. First, the Union must simply focus on the exclusive competencies its architects gave it, which are already orientated towards prosperity. These include the customs union; the competition rules necessary for the functioning of the internal market; monetary policy for the Member States whose currency is the euro; and a common commercial policy.11

The internal market has only one definition: the free movement of goods, services, capital, and workers. It is against these standards that it should be judged, exclusively and fully. Every other issue of political expediency – from the energy use of household appliances to the length of the work week – is not an internal market issue, despite what has been said to justify further legislation.12 While many of these issues are important, the Union provides for their regulation through Member States at the central, regional and local levels under the subsidiarity principle.13

This is not a repudiation of social concerns. Only a prosperous Europe can fund the welfare state. As Article 2 of the Rome Treaty of 1957 already spelled out, the internal market constitutes the foundation for improvements in standards of living:

The Community shall have as its task, by establishing a common market and progressively approximating the economic policies of Member States, to promote throughout the Community a harmonious development of economic activities, a continuous and balanced expansion, an increase in stability, an accelerated raising of the standard of living and closer relations between the States belonging to it.

The treaties that have shaped the European Union provide the solutions that we need. Yet, today, the core business of Europe, the internal market, is a fiction. The European Commission, which should be its referee, has stopped calling fouls. Infringement cases are down 75 percent from a decade ago. And the time needed to resolve them has dramatically increased.14 The European Union needs to stop wading into new policy areas like housing or animal welfare and get serious about enforcing basic internal market rules. This is a question of will and of prioritization, not capacity.

To face the great transformation ahead, Europe needs both an innovation system and creative destruction. We lack in both areas, but we are particularly weak in creative destruction. The ECB has pointed out repeatedly that Europe’s failure to kill zombie firms crowds out credit for healthy firms.15 We must stop defending legacy assets and build a system that accepts both market entry and exit as the basic conditions for innovation.

This requires a firm commitment to economic dynamism. It means we must actively seek and eliminate barriers to entry that favor incumbents, such as special rights, subsidies, or skewed regulations from banking to telcos, from energy to agriculture. We must support market exit through streamlined bankruptcy laws and flexible labor rules. Market exit is not failure; it is how we reallocate assets, people, and resources from old businesses to new ideas. This entire system must be built on a foundation that allows entrepreneurs and inventors to reap the rewards of their success, supported by secure property rights, deep financial markets, and unwavering legal certainty for risk-takers.

Some risks require prudence. But currently, Europe’s risk paranoia is killing its future. Our generalized precautionary approach disincentivizes the bold bets that lead to breakthroughs, from AI or genetic engineering to venture capital. Innovation requires risk-taking. We should enable it, not regulate it out of existence.

Ukraine provides an extraordinary example of this vision. It is much poorer than any EU Member State but it has rapidly and affordably fielded military capabilities none of them have, in large part because it has trusted and enabled its citizens’ ingenuity. If Ukraine is still standing today, it is because of the resilience of its people, but also thanks to the efforts of its hundreds of ‘tinkerers, tweakers, and implementers’ in building, testing, and deploying new ideas, especially with drones.16

Ukrainian Border Guard Servicemen with DJI Mavic Drones. Photo by ArmyInform. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Europe led the industrial revolution in part thanks to its political diversity: competition among states drove societies to seek and reward the best talent and innovators. Variation is a strength. What works for five countries may not work for twenty-seven. Instead of forcing uniformity, we should embrace ‘variable geometry’, that is, letting groups of willing countries cooperate more deeply on shared goals.

Committing to diversity requires genuine mutual recognition. If a product is safe enough to be sold in Lisbon, it should be safe enough for Berlin. We should not burden traders with the task of removing local barriers to trade through judicial remedies in the target country, let alone expect them to do so. Stephen Weatherill has shown that a pure mutual recognition model does not exist in the European Union. Instead, the European Union has a model of non-absolute or conditional mutual recognition. European Union law in reality allows Member States freedom to restrict imports of goods and services and only forces them to demonstrate why imports are not good enough for the home market under a specific procedure. Traders are therefore subject to ‘an unstable litigation-driven trading environment of inter-State regulatory diversity’.17 The business of business is business, not litigation.

A genuine model of mutual recognition lets different approaches compete to find what works best and removes egregious obstacles to trade through swift judicial redress at the European level. We must create simple and clear rules that free competition instead of centrally planning our economy by regulatory fiat.

Europe’s frenzy of regulation has been predicated on the existence of free lunches. For instance, climate laws have been sold as leading to job creation and innovation (the ‘green deal for jobs’) not just as the solution to climate change. Citizens were asked to swallow make-believe propositions, like the idea that fighting global warming would be free of economic cost.

Similar Nirvana fallacies have been observed in other domains, like migration, trade policy or digital regulation.18 Honest policymaking requires accepting that goals often conflict. A decision to prioritize one objective, whether environmental protection or data privacy, generates a cost somewhere else – often competitiveness and innovation. We must acknowledge and face these trade-offs.

This does not mean that we should give up on the dream of political integration. But our inability to generate prosperity cost us the support needed to achieve it. In order to achieve everything else, our proposal is that the European Union concentrate on its core function – prosperity – for the foreseeable future. Other projects are and should still be possible, but, to quote Mario Draghi, they “would be built through coalitions of willing people around shared strategic interests, recognizing that the diverse strengths that exist in Europe do not require all countries to advance at the same pace.”19 The European Union has 450 million citizens. They are educated, tolerant, and committed to freedom and democracy. The continent is rich, and, for now, large. This is not a weak starting position. But the Union has become reactive, trapped by crises and caught on the back foot by events, busy protecting what it is instead of thinking about what ought to be.

A renaissance is possible. A much better Europe is feasible if it stops building walls of regulation, lets innovation happen, and focuses on prosperity above all else. It must trust its people and let them build.

Legal reforms

We can take six practical steps now to reorient Europe towards prosperity. At a minimum, we must: enforce the internal market rules, stop directives from fragmenting it in the name of ‘harmonization’, facilitate the growth of entrepreneurial firms, focus the union on its priorities and limit the excessive flow of legislation without regard to cost.

1.Eliminate the usage of directives

In 1979, the European Court of Justice ruled in the Cassis de Dijon case that goods lawfully produced and marketed in one Member State must flow freely to all others. The principle of mutual recognition was born. Unless there is a general public interest at stake, Member States cannot enforce their own domestic laws to bar imported goods.

While mutual recognition should have delivered an internal market, forty-five years later, businesses must still comply with a maze of national barriers. France imposes unique carbon tests on imported diesel. German Länder require separate fire safety certifications for construction materials already approved elsewhere in the European Union. Spain blocks food with compliant labels. Denmark banned cereals sold safely everywhere else in the European Union. Varying national recycling logo requirements for paint create needless complexity for products that already conform to European Union standards, forcing manufacturers to maintain separate inventories for each country.

The solution is to abandon directives entirely.2020. Where this is possible. In some areas, directives are required by the Treaty. Letta offered to deprioritize directives relative to regulations. Our proposal is more drastic. We want a moratorium on the usage of directives. Note that the European institutions should also avoid fake regulations that work de facto as directives, maintaining lots of room for MS to introduce national implementations. These legal instruments betray their harmonizing purpose. Too often, Member States shirk on their duty to transpose directives. Worse, the abstract, broad, and general language of directives gives Member States opportunities to add local requirements.21 Businesses end up facing 27 different versions of supposedly ‘common’ rules. European Union lawmakers have tried to mitigate this problem by issuing increasingly prescriptive directives. The result is that directives today often reach the same level of detail as regulations. However, directives do not enjoy equivalent direct applicability in court.22 They must still be transposed. A better state of affairs would be achieved if regulations were to become the default, allowing traders to benefit from their unconditional applicability in litigation.23

2.Specialized Commercial Courts

The internal market’s main weakness is enforcement. When Italian regulations illegally block a French trader, that company faces only bad options. It can file a complaint with the Commission and wait years for action that may never come; sue before Italian courts only slightly familiar with European Union law; operate illegally and hope to reach the European Court of Justice through proceedings brought against it; or simply give up.

Under that model, effective mutual recognition is a pipe dream.24 The issue is this: inter-state barriers to trade can only be taken down through administrative and judicial enforcement. The unlikely prospect that traders will commit time and money to complaints and litigation leaves Member States essentially free to regulate domestic markets.

We propose that the European Union create Specialized Commercial Courts with exclusive jurisdiction over internal market violations by Member States. This structure fits well with treaty law which allows for specialized tribunals attached to the General Court to hear proceedings in specific areas.25 Specialized Commercial Courts would have many benefits, including legitimacy, expertise and speed. This is crucial. Any business facing discriminatory or non-discriminatory trade barriers could bring proceedings directly under English-language procedures. Decisions would be handed down within 180 days. The Specialized Commercial Courts would issue European Union-wide injunctions, award damages for lost profits, and their rulings would bind all Member States – when one country’s licensing requirement falls, similar requirements elsewhere become unenforceable.

Judgments from the Specialized Commercial Courts would be subject to appeal to the General Court only on points of law, and without subjugation to other policy goals.26 The entire system – five regional courts plus a limited appeal on points of law to the General Court – would cost less than what Europe loses due to trade barriers in a single week.

3.Federal field preemption

European and national laws do not suspend each other. They add up. This means that traders face a regulatory thicket, which only gets denser as more national, regional, and local regulations are introduced. Right now, banks answer to European supervisors, national central banks, and local regulators simultaneously. According to the Draghi report, there are over 270 digital regulators in the European Union, each interpreting “common” rules individually.

The solution is that when the European Union regulates in areas of exclusive competence and internal market legislation, all national, regional, or local rules in that specific area cease to apply. This is the so-called automatic field preemption.

This is not a proposal for an imperial European Union with centralized powers. As said before, there ought to be a drastic narrowing of the spectrum of areas governed by European Union law. The European Union should focus only on core economic functions. But when Brussels acts within its exclusive competences, or for the internal market strictly understood, the result must be true unification.

4.A 28th regime that is appealing to businesses

The idea of a 28th regime – versions of which have been proposed by both the Letta and Draghi reports – is to give up on harmonizing 27 different corporate systems, which often accords to the lowest common denominator, and instead create an outside option for firms. In practice, Portugal would not need to adopt German corporate law or vice versa, as there would be a European alternative that companies can embrace if it serves them better.

Several 28th regimes for business have been tried, and every single one failed.2727. Amongst those tried: the European Economic Interest Grouping (EEIG), Societas Europaea (SE), Societas Cooperativa Europaea (SCE) and Societas Unius Personae (SUP). On the SCE, specifically, 18 years since the entry into force of the founding Regulation, there were only 113 registered in 30 EU/EEA countries, of which 75 were active. See Report on Council Regulation (EC) No. 1435/2003 of 22 July 2003 - Statute for a European Cooperative Society (SCE). To see what can go wrong, consider the European Company (Societas Europaea, SE). Introduced in 2004 the SE has been a complete failure. Amongst 23 million corporations registered in the European Union, only between 3,000 and 5,000 are registered as European SEs. Most of them are large firms. Why? First, the statutory conditions for the formation of SEs require businesses to incur high set-up costs and follow time-consuming and complex procedures for incorporation. This has tended to favor large firms.28 Moreover, the law embodied a high number of referrals to national law and burdens in terms of employee participation.29 This forced companies and investors to navigate a complex web of rules: the SE Regulation, the national laws implementing the SE, the underlying national company law, and the company’s own statutes. This self-inflicted flaw stripped the SE of its core utility: giving small and medium-sized firms scale through simple and swift pan-European incorporation.30

As the discussion in Europe stands right now, this is the most likely fate of this new proposal. A leak on the European Commission work program for 2026 says the proposal will take the form of a directive to implement this regime, which means that, sometime in the future, after years of national debates on its transposition, each country will have its own 28th regime.

It is essential that this time the European Union gets it right and creates a regime that is truly comprehensive and appealing for businesses that want to scale up across Europe, and for venture capital that wants to invest, and crucially, exit, in Europe.

The US demonstrated the power of this solution when it allowed companies to bypass state securities laws by being regulated at the federal level – late-stage firms became four times more likely to attract out-of-state investors.31 The European Union could achieve similar results by letting businesses opt into European rules rather than forcing all Member States to abandon their national systems. This would also go some way towards unifying capital markets.

Countries that wish to maintain their legal traditions can keep them. Businesses seeking European scale can bypass them. Competition between the 28th regime and national systems would reveal which rules promote economic efficiency and which ones protect incumbent’s rents.

The 28th regime needs to be a fully supranational (e.g. with no appeal to national laws) set of rules such that companies voluntarily prefer it.32 Incorporation, as well as the entire legal life cycle from formation to dissolution, should be fully digital. To avoid the fate of the European SE it should contain provisions on employee involvement. Of course, that does not exclude the company from being subject to the mandatory public policy laws of the Member States in which it operates. These companies should fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the new Specialized Commercial Courts. The contents of the regime should be to govern the internal affairs of corporations (corporate governance, conflicts of interest, fiduciary duties, shareholder rights, and capital structure) and leave maximum freedom for company specific procedures. Statutory requirements, formalities, and involvement of intermediaries should be kept to a bare minimum.

5.Rely on existing institutions when possible

It is an arresting fact that much of the European Union’s expansion has taken place in areas where existing institutions already operate. Fundamental rights is the obvious example. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe, which has countries such as the UK or Switzerland as members.

Instead of joining this long-standing system, the European Union built its own. It justifies this duplication by insisting on the idea of an ‘autonomous legal order’ – a self-contained legal system. This doctrine is often invoked as a pretext to set up redundant, European Union-specific institutions and rules. In the case of fundamental rights, this approach is not just poor practice; it arguably violates the European Union’s own law. Article 6(2) of the Treaty on European Union requires the Union to join the Strasbourg Court’s system, not compete with it.33

Now, a worthwhile policy would consist of systematically determining which other existing institutions the European Union could use to discharge some of its core missions. For example, it would intuitively make sense for the jurisdiction of the Unified Patent Court to be expanded to also hear European Union trademark or copyright disputes.

6.Reform legislative practice

Once adopted, European Union law becomes eternal law. It cannot be written off, even if wrong. Of course, most, if not all, European Union regulations or directives contain a review clause. Many temporary law and policy programs have become permanent. New regulatory structures entrench interests and are hard to dismantle. National regulatory authorities (NRAs) in network industries like telecoms illustrate this problem. Created to open monopolistic markets, they were supposed to hand over their powers to national competition authorities (NCAs) following liberalization. Decades later, the European Union has both NRAs and NCAs, adding compliance costs to industries no longer in need of market opening reforms.

To solve this, review clauses should be replaced with sunset clauses. Unless evidence shows a persistent market failure requiring maintenance or reform of a regulation or directive, the presumption should be that once a set period has elapsed, the instrument is no longer useful. Combined with rigorous impact assessment and productivity boards, sunset clauses would create natural pressure toward regulatory efficiency.

Moreover, the European Union fails at submitting new rules to a rigorous analysis of their costs and benefits. The Commission does have the duty to run an initial cost and benefits analysis of draft legislation. However, the Parliament and the Council, when they rewrite the law, often in private meetings (called ‘Trilogues’), are not required to check the costs and benefits of their own changes. This loophole leads to duplicative and often inconsistent legislation. Political deals get made without anyone knowing their true cost. This allows politicians to avoid confronting the cost that new rules imposed on citizens and businesses.

To fix this, we need to make cost-benefit analysis (in European Union parlance ‘Impact Assessment’) an integral part of the entire process. First, the Parliament and the Council must each set up their own independent teams of experts to assess the impact of new laws. Second, a new rule must require them to use these teams. Whenever a change is proposed to a law that alters its purpose, key terms, or costs, the team must produce a short, public report on the effects. This report must be available before a final deal is made, so that everyone is working with up-to-date information.

This last change can deliver two benefits. Laws that state their costs and benefits strengthen democracy: voters and representatives can judge the trade-offs. Laws that face their economic impacts improve competitiveness: legislators must prove their rules do more good than harm. If this slows the machinery that produced 13,000 legal acts between 2019 and 2024, so much the better.

The path forward

For Europe, growth is existential. It is the precondition for every other political goal we may have, including our very survival. For too long, it has been traded off for other priorities, even though those priorities cannot exist without growth. In trying to do everything, we have hindered innovation, investment, and prosperity.

Fortunately, European institutions have a long track record of growth. They did it once, in the three decades after the Second World War. They did it again in Eastern Europe, in the last three decades. Poland entered the millennium at 47 percent of the European Union average income and today stands at 93 percent. Romania climbed from 37 percent to 83 percent. Lithuania surged from 39 percent to 96 percent. Few institutions can lay claim to not one but two of the great growth miracles in the past century.

But neither was achieved through the competencies that have been layered on in the last twenty five years. They were products of economic integration and solid European institutions. The European Union must learn from its own successes, and loosen the chains that hold it back from prosperity. The constitution of innovation we propose offers a different path, built on limited objectives, clear rules, and strong enforcement. This constitution does not require a new treaty. It requires will.

Thank you for this paper. It is by far the most intelligent and realistic description of what welt wrong with the European projection. I hope tour thought will disseminate. In fact it should go viral given how to the point it is. Thanks again. I have subscribed ans I'll keep reading you.

Thank you for your clear thinking and persuasive writing!

Just two small thoughts that popped up in my head:

1. I think an "unstable litigation-driven trading environment of inter-State regulatory diversity" very much describes how my American friends see their own economic area. And if the US is also a regulatory mess, to stay competitive vis-à-vis the US should depend on something else entirely, no?

2. I'm normally interested in the competitiveness of companies or industries, not whole economic areas, but I do think considering particular industries may provide a litmus test of sorts, ie., would your suggestions fix European tech and the car industry? These are under pressure largely from Silicon Valley's network dominance and Chinese subsidies, respectively, and I do fear that any solution that doesn't solve their problems may end up not solving many others either.. (yes the sector lacks creative destruction but there ARE barbarians at the gates too!)