Learning to love Baumol

As people get richer they spend more time in Europe

Last week I read the memoirs of Henry Adams. He chronicles American life in the second half of the nineteenth century and his experience of industrialization. As they become richer, the Americans in his life consume more goods. But the other way their wealth manifests itself is through more leisure time, and increasingly frequent and lengthy trips to Europe.

This is a universal pattern. As a country develops, its citizens spend less time working and more time in Europe. The industrializing English invented alpinism; the Gulf monarchies spend their winnings on yachts in Provence.

This should favor Europe in a future of mass automation. Two weeks ago we wrote about how the Baumol effect would lead the continent to miss the upside from AI. Certain sectors, like hospitality, education, and healthcare, are hard to automate and employers in those areas need to compete for workers with sectors that do. As a result, as productivity rises elsewhere, wages have to rise in the non-automated sectors as well.

The Baumol effect explains why the prices of housing and hospitality have risen as other industries have improved their output. The problem for Europe is that a greater share of its economy is dedicated to the Baumol sectors than in other regions:

Projected age-related public expenditures will rise from 25% today to 29% of GDP by 2070 in Europe. Tourism drives one tenth to one fifth of GDP in Spain, Italy, and Greece. Public administration employs nearly a quarter of the workforce in many European countries.

But the ‘loser’ in the Baumol effect is the individual paying for the string quartet, not the violinist.

If the stagnant services are exports, then this relative movement in prices is favourable to the exporter, who may experience rising wages even if his own productivity has not risen. It should allow Europe to capture a share of other countries' gains from AI even if it is slower to automate itself.

The channel above is not the traditional Baumol mechanism, which relies on workers being able to switch between high productivity and low productivity sectors and where employers compete for talent. It is more similar to rising foreign demand for a natural resource leading to an increase in price and revenues.

But the outcome is similar to Baumol: rising productivity in some sectors pushes up wages in sectors which do not see productivity gains. Prosperity elsewhere raises the demand for luxury goods and services, of which Europe produces a vastly disproportionate amount.

Only a small share of a rich individual’s income is spent on services imports from abroad, so receiving it only gets a country so far. Naples is much richer than it would be without tourism, but still quite poor. Major tourist destinations in developing countries are regional outliers, but are much closer to their regional averages than to developed countries. Tourism overall only generates 10 percent of the European Union’s GDP.

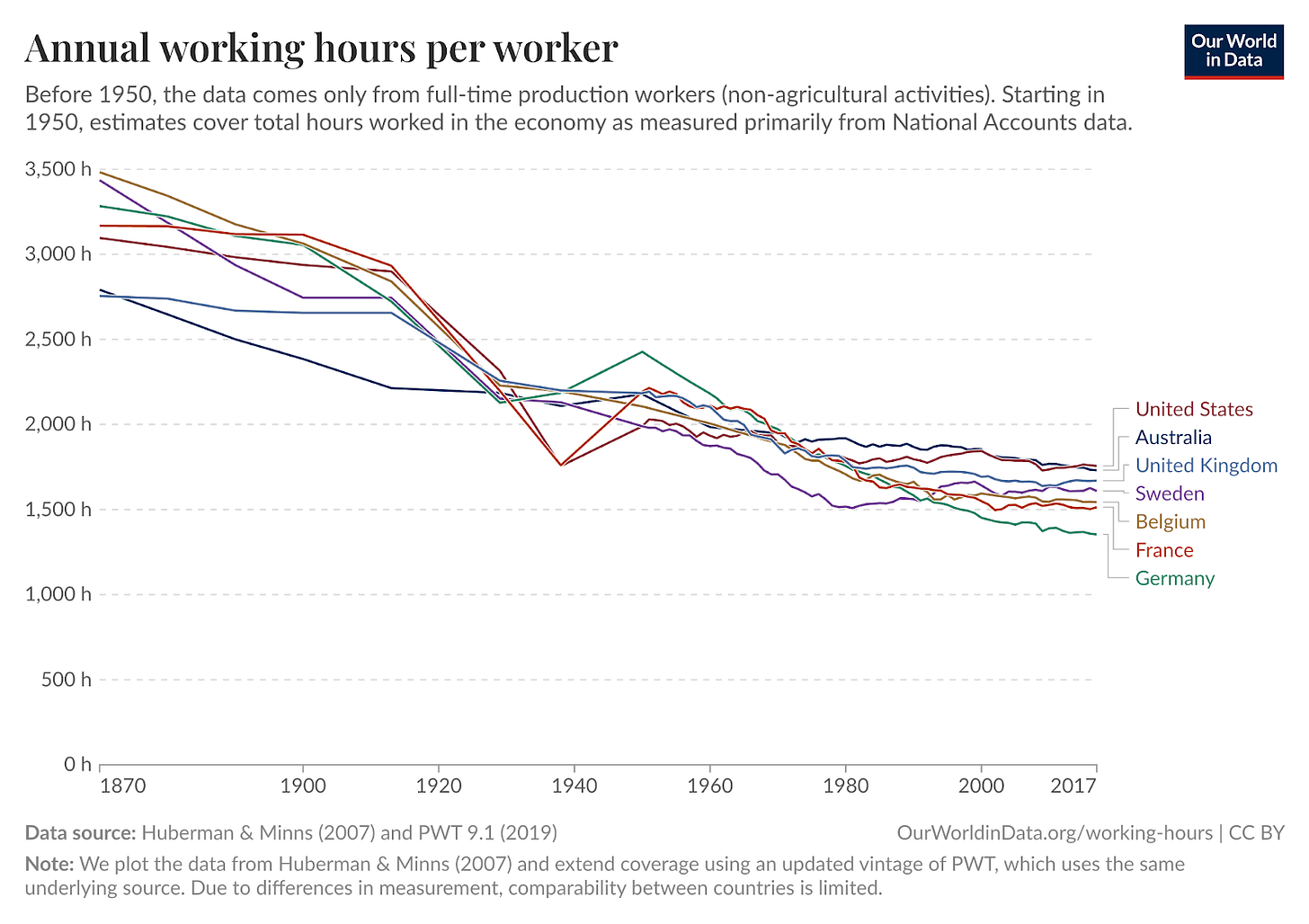

But this has been the case when individuals only dedicate small shares of time and income to vacations. Development increases those proportions: industrialization led to a forty percent decrease in hours worked in England and sixty percent in Germany. The much greater potential automation following AI should have a similar effect.

For wealthy individuals around the world, the desired good is a European vacation. Visitor numbers have risen 78 percent since 2004, reaching 747 million in 2024. For the income brackets below that there are luxury goods; for those above there are yachts and sports clubs to purchase. Northern Europe's wealthy retirees already spend several months per year on the coasts of Spain, Italy, and France. The rest of the world may want to join them.

Like all modern growth before it, if growth rapidly accelerates anywhere due to large-scale deployment of AI, much of this newfound prosperity should find its way to Europe's real estate, restaurants, theaters, and hotels.

Dutch disease

There are problems with this development mechanism. Relying on exports in a single sector can lead to a form of the Dutch disease – other sectors become weaker, and growth becomes unbalanced. And, the tourism boom would bring severe distributional issues.

In the classic Dutch disease case demand for a resource leads to the appreciation of the real exchange rate, which benefits owners of the desired goods but squeezes other exports as they become more expensive.

The same can happen with tourism, as it did in Spain and Italy in the run-up to 2008, when the tourism boom drove up real wages and lowered exports from other sectors.

There is one important difference: the fear with natural resources is that they will run out, leaving a country with weaker alternatives in its aftermath. Roman ruins will not run out, although the general outcome is the same: demand for one export sector weakens other sectors.

Even without other sectors weakening the gains would be extremely uneven. Today only one in twelve Europeans currently works in tourism. The curse of the other eleven is that they have to compete for Europe's services with the rest of the world. This is particularly the case in real estate: a Spaniard intending to buy a home in a coastal town competes with alternate uses such as hotels and vacation rentals. Some cities have banned these secondary uses to protect their existing inhabitants. Large tourist destinations like Amsterdam, Venice and Barcelona have large political movements seeking to lower tourist arrivals.

Optimizing for foreigners could be distortionary in more ways: aggressive preservationism probably makes a city more attractive to rich foreigners, as attested by western London and inner city Amsterdam. But a lack of new construction leads to misallocation as existing residents cannot live where they would be most productive.

Other countries will have to figure out how to redistribute uneven gains from automation. Europe will have to figure out how to redistribute the gains from AI automation and the gains from leisure driven by the gains from AI automation.

But the upshot is still that mass automation would almost certainly bring Europe a significant windfall, as previous growth has also done. The Swiss miracle in the late 19th and early 20th century was driven by watches and banking, but also by tourism, which grew enormously as the rest of Europe industrialized.

New entrants may arrive: AI could give us more potent forms of entertainment, even if for now there is no metaverse that can recreate the Amalfi Coast. But the supply of leisure destinations has been growing for decades; this has not hurt Europe because the growth in demand has simply outpaced it.

Sam Altman recently published an essay on the world after the advent of artificial general intelligence. He writes that "if history is any guide, we will figure out new things to do and new things to want." That is mistaken: history shows that as the world gets richer, it chooses to have more of the same – leisure time – and to do the same with it – spend it in Europe on vacation. Much of the continent may be lucky for it.

Great article. This one and the previous Baumol article on your blog are very well-written.

It seems like the upside for Europe of the Baumol effect extends well beyond tourism. Baumol says that low productivity growth sectors tend to grow faster as a share of the total economy. So wouldn't countries which are specialized in producing services tend to grow faster than countries which are specialized in high-productivity growth sectors like manufacturing? It seems like a great strength of the United States and Europe is that they have highly productive service sectors (China, on the other hand, seems to be very unproductive in services: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2024/276/article-A002-en.xml). If anything, the more worrying thing about Europe seems to be that, compared to the US, Europe is more specialized in manufacturing. If the Baumol effect is strong, then manufacturing will continue to shrink as a share of the global economy, and thus European manufacturing centers will likely see low relative growth rates.

Now, while I think countries which specialize in producing services will tend to benefit from Baumol, I think countries which disproportionately consume services may be harmed by Baumol (since services will become relatively more expensive). So there could be countervailing forces for a region like Europe, which consumes more services due to its high income and older population. But is Europe really much more poorly positioned than the rest of the world in this regard? It seems like the demographic situation in East Asian countries is much worse, especially considering Europe's ability to grow its working age population through immigration.

One final thought: in this blog's previous piece on Baumol, healthcare was mentioned as a low productivity growth sector. I know that's true in official statistics, but I think there's good evidence that those statistics are drastically understating the massive improvements in healthcare that we see over time: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/508033. I would guess that due to the high income elasticity of healthcare demand, healthcare tends to grow as a share of the global economy even though it has high productivity growth (that is, the Baumol effect doesn't apply to healthcare).

It sounds more like a surrender for Europe which, don't get me wrong, can also be its only way, given the adversion for high-productivity sectors and AI in general. But, those solutions/suggestions to me sound very generic, meaning, that scenario is already happening even without the expected AI freedom. Most European countries, especially southern, only know low-productivity sectors as miraculous recipe for their economy. And now already, they are dealing with externalities without really facing it: they just do nothing. So, those suggestions become even more difficult to implement since they should have already be in place now.