Is the euro ready to become a safe haven?

Institutions matter, especially in crisis times

My coauthors of “Crisis Cycle: Challenges, Evolution, and Future of the Euro”, John Cochrane and Klaus Masuch are joining me for this blog. The book is forthcoming in Princeton University Press on June 17th. If you are interested in it, do preorder it, e.g. on Amazon. We understand that many future shipping, promotion, and stocking decisions depend on this crucial gauge.

Markets are in turmoil, with signs of a flight from dollar assets. Is this turmoil an opening for the euro to challenge the dollar as “reserve currency” or for euro debt to replace US treasury debt as “global safe asset”? Our forthcoming book, “Crisis Cycle: Challenges, Evolution, and Future of the Euro,” helps to answer that question.

In a reversal of historical patterns, international investors seem wary of U.S. assets, offloading simultaneously bonds, stocks, and the dollar, sending prices down. As Noah Smith recently noted, this looks like capital flight, more often seen in troubled developing economies. When Trump took office, a dollar bought almost 97 euro cents. Today, it buys only 88.

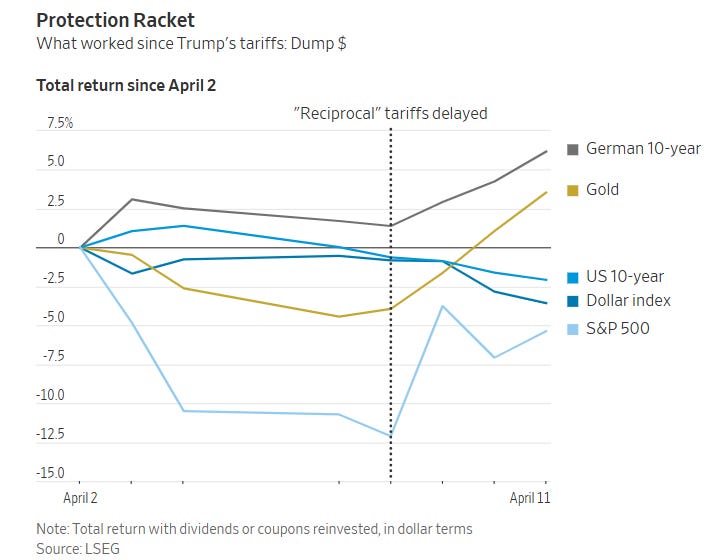

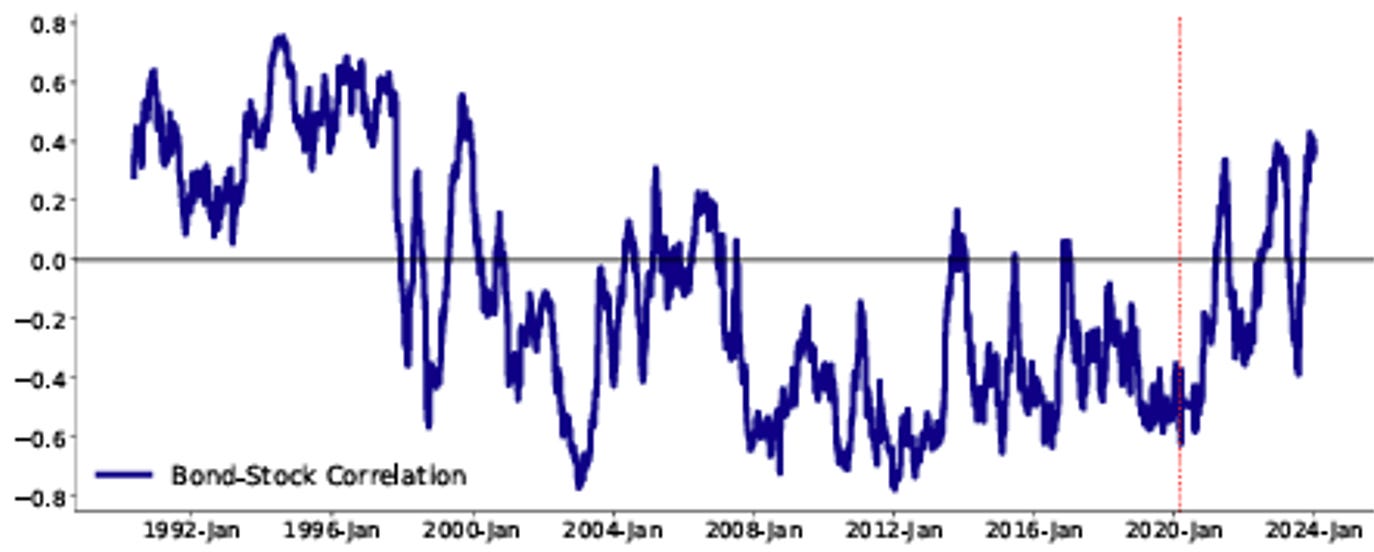

German government bonds have recently delivered better returns than U.S Treasuries, by the widest gap in decades, according to Bloomberg’s calculations. During the first two decades of this century, US bonds used to be a good hedge against market risks. In bad times, treasury yields would fall, and prices would rise as people sought to buy them (see chart below from a recent post by Hanno Lustig).

.

That is why foreign investors and central banks held treasury bonds in large amounts, even at relatively low average returns. If US treasury bonds are no longer the “safe asset” in bad times, people will desire fewer of them, and US real interest costs will rise.

How will the current turmoil affect the euro?

So does this turmoil presage a turn from dollar to euro? It depends on whether euro institutions are reformed and how they handle the exchange rate, capital, trade, and fiscal fallout from the American situation.

A flight from US assets would initially continue to strengthen the euro. If the ECB focuses on its price stability mandate, it would likely let the euro rise rather than intervene to soften the exchange rate. This development benefits the eurozone by enhancing its safe-haven status, lowering borrowing and debt-service costs, and giving the central bank more room to lower interest rates later without endangering price stability.

But the exchange rate rise will hurt exporters, and trade complaints will rise in Europe as well. More deeply, the tariff and uncertainty shocks are classic “supply” or “stagflationary” shocks for Europe as well as the US. A trade-induced recession will also worsen fiscal stress, as governments respond as usual with bailouts and stimulus.

The ECB was set up to focus on inflation only and to ignore output, employment, and specific sectors. But it will be hard-pressed to do so. The ECB reacted to Covid-era shocks by buying huge amounts of sovereign debt and leaving interest rates untouched for almost a whole year after inflation had reached 3%, thereby allowing inflation to surge rather than suffer worse economic outcomes.

The fiscal impact of the current turmoil is likely to vary significantly across countries. America’s retreat from support for Ukraine and Europe more generally requires much greater European defense spending. That shock affects euro states closest to Russia most severely.

Trade turmoil hits export-oriented economies like Germany and the Netherlands hardest. The political nature of US trade exemptions will create further differences. For example, the recent electronics exemption (whose scope and duration is unclear) could directly benefit the Netherlands through ASML's equipment exports. Countries exporting tourism and services may remain relatively insulated. But not necessarily: a global recession will affect even those industries, and foreigners must be able to sell goods in Europe to obtain the euros to spend here. This varied impact may actually provide some relief, as more indebted European countries are overall less exposed to both the defense and trade shocks. (Italy may be an exception with its machine tools exports to the US.) Each country will try to protect their most vulnerable or politically sensitive sectors, adding to fiscal stresses.

These events surely will put upward pressure on some countries’ bond spreads. The ECB will face pressure to support sovereign bond prices of individual countries. The ECB has grown accustomed to tamping down most increases in yield spreads as due to “dysfunction,” and creditors have grown to expect such intervention.

Some will argue that smaller spreads enhance the international role of the euro, and lead to the path we started with. But the ECB must resist this pressure. Low bond spreads only attract “safe asset” investment if they are earned by fundamentals, not when they are artificially supported by central bank intervention. European institutions should prioritize transparency, predictability, and stability, not complex window-dressing.

A full-blown US financial crisis—perhaps triggered by fears of capital controls, default, taxation, or other ways to expropriate debt holders (especially foreigners) without triggering a credit event—is not out of the question. Such a crisis would also affect Europe more severely. It is not clear that bond investors would fly to the euro rather than fly from all sovereign debt. The Greek sovereign debt crisis did not spark a rush to Italy after all; precisely the opposite was feared. And Europe's banks are still stuffed with sovereign debt. The ECB will face even more pressure to monetize sovereign debt.

In such a crisis, the US Federal Reserve is likely to respond with inflationary policies, as it did in 2020: buying large amounts of debt, bailing out financial institutions, and holding down interest rates.

The ECB will then face a critical test. By holding firm to its price stability mandate, allowing fundamentals to determine bond prices, and resisting imported inflation pressure—as Switzerland has done in the past—the ECB could build tremendous trust, making the eurozone a more attractive currency area. The ECB's independence and mandate offer protection here if leaders adhere to principles. But the developing cracks in the euro’s fundamental structure, the ECB’s huge bond holdings, and widespread expectations that the ECB will intervene in any hiccup make it very difficult for the ECB to hold firm.

Weaknesses in the euro design

The Eurozone faces deep challenges due to its basic design, and how that design evolved in the wake of previous crises. Eurozone monetary policy is run by the ECB. But fiscal policy—taxes, spending and debt—stays with the 20 separate nations. This structure leaves an obvious potential problem: governments might borrow, spend, be unable to repay, and count on the ECB to bail them and their creditors out with newly printed euros.

The architects of the euro were well aware of this problem and sought to manage it in the rules of the euro: the ECB could not directly finance governments, states faced debt and deficit limits, and countries could not bail each other out. But key pieces were missing. Crucially, there was no clear plan for handling a country facing deep debt trouble within the euro. The euro setup did not include a mechanism for sovereign default, nor an IMF-like institution that can help countries in trouble to avoid default. Furthermore, banks are allowed to treat sovereign debt as a risk-free asset, so sovereign debt troubles quickly imperil the banking system. This lacuna is understandable, as one does not want to spend too much of a wedding night on the prenuptial agreement. The founders of the euro understandably may have expected further elaboration of its structure over time. But that weakness was never addressed, and it came to bite.

The missing safety valve meant that when the sovereign debt crisis hit—governments nearing default, and large banks threatening failure—the planned and necessary separation between monetary and fiscal policy broke down. The ECB felt it had to step in, buying government bonds, an action it had previously avoided. Emergency rescue mechanisms were hastily established.

These actions stopped immediate collapse but damaged the original design. They created expectations of future bailouts, weakening incentives for countries, banks, and even euro-wide institutions to act responsibly. Over the years, the ECB has stepped in repeatedly, buying more debt or announcing to do so in future contingencies, tamping down rises in yields, especially of countries with high debt under the banner of market “dysfunction.”

One does what one must in a crisis, but one should take action after the crisis to repair the damages. The failure to reform after each bailout is the major problem.

The envisioned separation between monetary and fiscal policy has now been largely erased. Everyone expects an ECB rescue. Fiscal policies, especially in large euro area countries, are not in much better shape than US fiscal policy, and loud voices advocate borrowing even more with little concern over repayment. Yet there are limits, even for central banks. We just saw one: inflation.

This gap between the necessary separation of monetary and fiscal powers and the expectations created by actual policies during crises remains the euro’s central weakness. As long as sovereign debt markets and sovereigns themselves are addicted to ECB support, as long as there is no clear mechanism for sovereign default or sovereign restructuring, as long as the banking system remains strongly exposed to sovereign debt, the ECB will face the same dilemma as in its previous crises, only larger and more immediately inflationary.

Seizing the Historical Moment

Our book identifies a detailed package of specific reforms needed to complete the eurozone's architecture. These changes would address historical weaknesses and missing elements, thereby strengthening the conditions for price stability and financial stability also in difficult times. As a welcome side-effect, such reforms would strengthen the position of the euro in the current global monetary uncertainty

Current dollar instability and global tensions provide the eurozone with a big strategic chance. Strong institutions are key to prosperity and stability. As faith in institutions seems to waver elsewhere, building credible, robust economic structures in Europe is the best way to offer the stability the world needs and enhance the euro's global role naturally.

The original euro structure was sound in principle but incomplete. Past crises exposed critical gaps, leading to quick fixes that undermined the system's foundations. Today's global challenges offer a compelling reason to finish the job.

Europe must also want to reform–and not just its monetary institutions. Europe needs to grow again, not least to strengthen public finances. Growth requires business creation and destruction, both essential for innovation, and removing suffocating regulation. But implementation of growth-enhancing structural reforms has been disappointing for many years. Instead, Europe is still too addicted to debt and borrowing. For example, many commentators cheer the abandonment of the German debt brake under the banner of Keynesian fiscal stimulus. Mario Draghi’s excellent diagnosis of Europe’s regulatory burden segued into a call to borrow even more money for government investment, despite the abundant waste of past efforts. Most of all, Europe still congratulates itself and the ECB for putting out any spark with rivers of new money. Yes, each time the fire was put out, but the larger and larger debts held in the ECB’s coffers, and the greater and greater fiscal carelessness it has engendered threaten a conflagration ahead.

Can the eurozone meet these challenges and fulfill its potential? Our book argues it can – provided Europe completes the necessary institutional reforms. Strengthening crisis management mechanisms, fiscal discipline, as well as banking regulation, and, thereby, financial stability is crucial not only to address historical weaknesses but also to establish a resilient eurozone capable of greater global economic leadership.

An appreciating euro and potentially lower yields would provide a window of opportunity. Europe can use this chance to implement the reforms needed for long-term strength.

A safe haven instrument must be liquid. The euro offers the government bonds of Germany, France and Italy. These bonds are liquid in small quantities but, in large quantities, operations begin to move the price. This is not true for US government bonds which are liquid in all quantities.