How Brussels writes so many laws

Explaining Europe’s extraordinary legal productivity

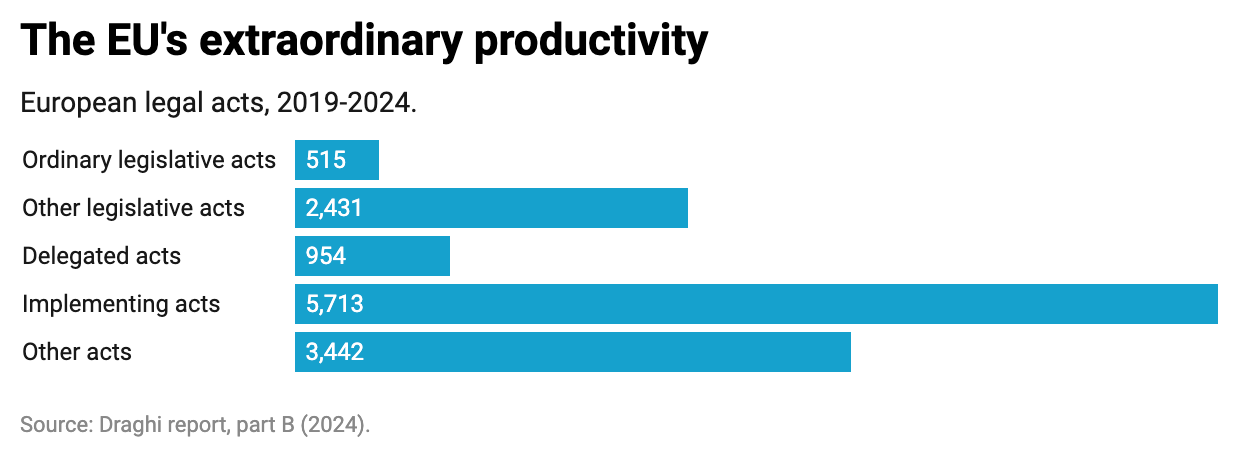

The central puzzle of the EU is its extraordinary productivity. Grand coalitions, like the government recently formed in Germany, typically produce paralysis. The EU’s governing coalition is even grander, spanning the center-right EPP, the Socialists, the Liberals, and often the Greens, yet between 2019 and 2024, the EU passed around 13,000 acts, about seven per day. The U.S. Congress, over the same period, produced roughly 3,500 pieces of legislation and 2,000 resolutions.1

Not only is the coalition broad, but encompasses huge national and regional diversity. In Brussels, the Parliament has 705 members from roughly 200 national parties. The Council represents 27 sovereign governments with conflicting interests. A law faces a double hurdle, where a qualified majority of member states and of members of parliament must support it. The system should produce gridlock, more still than the paralysis commonly associated with the American federal government. Yet it works fast and produces a lot, both good and bad. The reason lies in the incentives: every actor in the system is rewarded for producing legislation, and not for exercising their vetoes.

Understanding the incentives

The Commission initiates legislation, but it has no reason to be reticent. It cannot make policy by announcing new spending commitments and investments, as the budget is tiny, around one percent of GDP, and what little money it has is mostly earmarked for agriculture (one-third) and regional aid (one-third). In Brussels, policy equals legislation. Unlike national civil servants and politicians, civil servants and politicians who work in Brussels have one main path to build a career: passing legislation.

Legislation is valuable to the Commission, as new laws expand Commission competences, create precedent, employ more staff, and justify larger budgets. The Commission, which is indirectly elected and faces little pressure from voters, has no institutional interest in concluding that EU action is unnecessary, that existing national rules suffice, or that a country already has a great solution and others should simply learn from it.

The formal legislative process was designed to work through public disagreement, with each institution’s amendments debated and voted on in open session. The Commission proposes the text. Parliament debates and amends it in public. The Council reviews it and can force changes. If they disagree, the text bounces back and forth. If the deadlock persists, a joint committee attempts to force a compromise before a final vote. Each stage requires a full majority. Contentious laws took years.

This slow process changed in stages. The Amsterdam Treaty (1999) allowed Parliament and Council to adopt laws at the First Reading if an agreement was reached early. Initially, this was exceptional, but by the 2008 financial crisis, speed became a priority. The Barroso Commission argued that EU survival required rapid response, and it deemed sequential public readings too slow.

The trilogues became the solution after a formal “declaration” in 2007, though the Treaties never mention them. Instead of public debate, representatives from the Parliament, Council, and Commission meet privately to agree on the text. They work from a “four-column document.” The first three columns list the starting positions of each institution, the fourth column contains the emerging law. The Commission acts as the “pen-holder” for this fourth column. This gives them immense power: by controlling the wording of the compromise, they can subtly exclude options they dislike.

Because these meetings are informal, they lack rules on duration or conduct. Negotiators often work in “marathon” sessions that stretch until dawn to force a deal. The final meeting for the AI Act, for instance, lasted nearly 38 hours. This physical exhaustion leads to drafting errors. Ministers and MEPs, desperate to finish, agree to complex details at 4:00 a.m. that they have not properly read. By the time the legislation reaches the chamber floor, the deal is done, errors and all.2

The European Parliament is the institution that is accountable to the voters. But it is the parliamentary committees, and their ideology, that matter, not the plenary or the political parties to which MEPs belong. Those who join EMPL, which covers labor laws, want stronger social protections. Those who join ENVI want tougher climate rules.

The committee coordinator for each political group appoints one MEP to handle the legislative file: the Rapporteur for the lead group, Shadow Rapporteurs for the others. These five to seven people negotiate the law among themselves, nominally on behalf of their groups. In practice, no one outside the committee has any say.

When the negotiating team reaches an agreement (normally, a grand coalition of the centrist groups), they return to the full committee. The committee in turn usually backs the deal, given that the rapporteurs who made it represent a majority in the committee, and the committee self-selects based on ideology.

Crucially, the rapporteurs then present the deal to their political groups as inevitable, based on the tenuous majority of the centrist coalition that governs Europe. “This is the best compromise we can get,” the rapporteur invariably announces. “Any amendment will cause the EPP/Greens/S&D/Renew to drop the deal.”

Groups face pressure for a simple up-or-down vote, and often prefer to claim a deal than doing nothing. MEPs who refuse to support the deal may be branded as troublemakers and risk losing support on their own files in the future.

Often just a couple of weeks after the committee vote, the legislation reaches the full Parliament to obtain a mandate authorizing trilogue negotiations, with little time for the remaining MEPs to grasp what is happening.

The dynamic empowers a small committee majority to drive major policy change. For example, in May 2022, the ENVI committee (by just 6 votes) approved a mandate to cut by 100% CO₂ emissions from new cars by 2035. De facto, this bans new petrol and diesel cars from that date.

Less than four weeks later, in June 2022, Parliament rubber stamped that position as its official negotiating mandate, with a “Ferrari” exception for niche sports cars. This four weeks left almost no time to debate, consult national delegations, or reconsider the committee’s position. From that slim committee vote, the EU proceeded toward an historic shift to electric vehicles continent-wide.

Similarly, the EMPL committee approved, in November 2021, the Directive on Adequate Minimum Wages, even though Article 153(5) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU explicitly excludes “pay” from the EU’s social policy competences. Co-Rapporteurs Dennis Radtke (center-right EPP) and Agnes Jongerius (center-left S&D) formed a tight alliance and gained a majority in committee, sidelining fierce opposition from countries like Denmark and Sweden that wished to protect their national wage-bargaining systems.

The committee’s text was rushed to plenary and adopted as Parliament’s position fourteen days later (in late November). The system let a committee majority deliver a law the Court of Justice ruled partially illegal in November 2025 precisely at the request of the Nordic states, striking down Article 5(2) on criteria for setting minimum wages.

The player you’d expect to check any excesses is the Council of Ministers from the member states, which represents national governments. But the way the Council participates in the drafting dilutes this check. The Council is represented by the country holding the rotating Presidency, which changes every six months. Each Presidency comes in with a political agenda and a strong incentive to succeed during its short tenure. With a 13-year wait before that member state will hold it again, the Presidency is under pressure to close deals quickly, especially on its priority files, to claim credit. This can make the Council side surprisingly eager to compromise and wrap things up, even at the cost of making more concessions than some member states would ideally like.

The Commission presents itself as a neutral broker during the trilogue process. It is not. By controlling the wording of the draft agreement (“Column four”), the Commission can subtly exclude options misaligned with its preferences. It knows the dossiers inside out and can use its institutional memory to its advantage. Commission services analyze positions of key MEPs and Council delegations in advance, triangulating deals that preserve core objectives.

The Commission also exploits the six-month presidency rotation. Research shows it strategically delays proposals until a Member State with similar preferences takes over.3 As the six-month Presidency clock winds down, the Council’s willingness to make concessions often increases. No country wants to hand off an unfinished file to the next country, if it can avoid it. The Commission, aware of this, often pushes for marathon trilogues right before deadlines or the end of a Presidency to extract the final compromises.

As legislation has grown more technical, elected officials have grown more reliant on their staff. Accredited Parliamentary Assistants (APAs) to MEPs, as well as political group advisers and Council attachés, play a large role. These staffers have become primary drafters of amendments and key negotiators representing their bosses in “technical trilogues”, where substantial political decisions are often disguised as technical adjustments.4

COVID-19 accelerated this. Physical closure increased reliance on written exchanges and remote connections, favoring APAs and the permanent secretariats of Commission, Parliament, and Council. The pandemic created a “Zoom Parliament” where corridor conversations, crucial to coalition-building among MEPs, disappeared. In my experience, they did not fully return after the pandemic. This again greatly strengthened the hand of the Commission.

Quantity without quality

The result of this volume bias in the system is an onslaught of low-quality legislation. Compliance is often impossible. A BusinessEurope analysis cited by the Draghi report looked at just 13 pieces of EU legislation and found 169 cases where different laws impose requirements on the same issue. In almost a third of these overlaps, the detailed requirements were different, and in about one in ten they were outright contradictory.

Part of the problem is the lack of feedback loops and impact assessment at the aggregate level. The Commission’s Standard Cost Model for calculating regulatory burdens varies in application across files. Amendments introduced by Parliament or Council are never subject to cost-benefit analysis. No single methodology assesses EU legislation once transposed nationally. Only a few Member States systematically measure a transposed law’s impact. The EU has few institutionalized mechanisms to evaluate whether a given piece of legislation actually achieved its objectives. Instead, the Brussels machinery tends to simply move on to the next legislative project.

Brussels’ amazing productivity doesn’t make sense if you look at how the treaties are written, but it is obvious once you understand the informal incentives facing every relevant player in the process. Formally, the EU is a multi-actor system with many veto points (Commission, Parliament, Council, national governments, etc.), which should require broad agreement and hence slow decision making. In practice, consensus is manufactured in advance rather than reached through deliberation.

By the time any proposal comes up for an official vote, most alternatives have been eliminated behind closed doors. A small team of rapporteurs agrees among themselves; the committee endorses their bargain; the plenary, in turn, ratifies the committee deal; and the Council Presidency, pressed for time, accepts the compromise (with both Council and Parliament influenced along the way by the Commission’s mediation and drafting). Each actor can thus claim a victory and no one’s incentive is to apply the brakes.

This “trilogue system” has proven far more effective at expanding the scope of EU law than a truly pluralistic, many-veto-player system would be. In the EU’s political economy, every success and every failure leads to “more law,” and the system is finely tuned to deliver it.

Draghi, M. (2024). The Future of European Competitiveness: .A Competitiveness Strategy for Europe

See “Ways to improve efficiency and transparency in trilogues and EU law-making” by Vicky Marissen. Report to the Ombudsman, 28 September 2015.

“We find that under codecision the Commission does indeed tend to introduce proposals on an issue when it is close to the Presidency on that issue. This may allow the Commission to obtain policy outcomes closer to its own preferences.” Philippe van Gruisen, Christophe Crombez, “The Commission and the Council Presidency in the European Union: Strategic interactions and legislative powers,”European Journal of Political Economy, Volume 70, 2021.

On the “technical versus political” trilogue issue, see Chapter 9 in “The Corridors of Power in Brussels:Informal Communication, Coordination, and Compromise in EU Trilogue Negotiations.” William Kjærgaard Egendal, PhD dissertation, May 2025. On the Covid impact on this balance, see page 304. Interviewees also note a rush to legislate after the Covid pause.

At some point you have to ask - at what point are we better off without the EU than with an EU that is constantly enlarging itself through the creation of these rules? There seems to be little public insight into this process because most national media organizations are simply too mediocre to ever investigate this stuff properly so there will not public pressure to create a framework to constrain the system.

What's the point of creating 13 thousand laws across 450 million people without any of the traditional organs of power:

Court system

Police

Taxation

Civil service

Army

The answer is that no one cares or is really paying attention besides some insiders in Brussels

To an outsider the eu has become a jobs program for civil servants and lawyers

Remember the whole strasbourg/Brussels thing?

The eu is by design a weak horribly complex institution that is holding Europe back.