Anatomy of an Error

On Spain’s Blackout and the EU Energy Policy

On Monday, April 28, 2025, at 12:32 PM, Spain lost all of its electricity. The shock drove home how electrified our lives are. I couldn't cook anything: our stove is now induction (electric) rather than gas. No 4G, no WiFi, no radio, no TV. No way to know, literally, what was going on. A war? A cyberattack? My neighbors certainly had hypotheses, each wilder than the next.

Cash? Sorry, I pay digitally. I did manage to persuade the corner store owner to let me pay for spare batteries in dollars at an exchange rate of his choosing. Our car is a hybrid, so if my mother had been in trouble (though how would I have known?) I could have driven down to Valladolid. But the gasoline pumps are electric, and stations were said to be running out of fuel.

It is not yet entirely clear what caused the initial blackout. What is certain is that the large amount of renewables on the grid (55% at that point) made any shock much worse:

“Electricity grids rely on alternating current, which is electricity that regularly changes direction, switching back and forth in a regular pattern. Frequency is the rate at which this current oscillates. It is typically measured in cycles per second, or hertz.

Maintaining a stable frequency is critical. The generators that power the grid and devices connected to it are designed to operate at specific frequencies. If they deviate, they can overheat, experience mechanical stress, or break. This affects everything from electric clocks to industrial motors. The nightmare scenario is a cascading failure. This is where uncorrected frequency deviation causes a small number of generator trips, worsening frequency problems, and causing more generators to cut out.

This is why the grid has a set of emergency measures. If frequency moves out of the 49.8 to 50.2 hertz band, it will begin shutting off power to parts of the system to restore balance. The electronic inverters that convert solar panels’ or wind turbines’ power to alternating current and connect it to the grid don't provide the inertia of large rotating generators, as they have none of the kinetic energy that stabilises mechanical turbines”

Just a few months ago, in polite politics, predicting that a European country would face a blackout due to renewable energy integration issues, would have made you a crank. Yet engineers at the European Network of Transmission System Operators foresaw precisely this scenario:

"Reduced system inertia is a natural consequence of the lower number of directly connected rotating masses of synchronous generators to the grid. The stability support traditionally granted by these generators... will no longer be available in an almost exclusively RES-dominated [renewable energy source] system. This will expose the electricity system to the risk of being unable to withstand out-of-range events like system splits that were previously manageable."

This problem is just the most dramatic manifestation of deeper issues with Europe's energy approach.

This winter, we experienced multiple times the consequences of the dunkelflaute, those periods of low wind and weak sun when renewable generation collapses. During the December event (which we covered on the blog), wind power fell to just 8% of normal output and solar to 7.7%. Spain was forced to cut electricity to factories to maintain residential service. In the UK, the grid came within 580 MW (1% of total generation) of shutting down during another dunkelflaute in January.

The solutions to this intermittency problem remain inadequate. You could build more transmission, but permits for even critical projects are not moving. The North Sea Ultranet, one such project, requires 13,500 different permits. Storage will be too little, too late. Germany's ambition is to build 52 GWh of battery storage by 2030, butit consumes more than 60 GWh every single hour during winter.

Finally, the transition (together with war) is making electricity extremely expensive for European industry. Deindustrialization — once a right-wing talking point — is clearly happening in parts of Europe, as the figure below in the Draghi report illustrates. Four chemical factories recently shut down in the port of Rotterdam due to high electricity costs. Germany has lost over 500,000 manufacturing jobs since 2022, with energy-intensive sectors particularly hard hit. The UK has seen its steel industry collapse as electricity prices there reach among the highest in developed economies.

We Europeans have come around on what we now view as the two great errors of the last two decades: neglecting defense and neglecting innovation. To that list we must add energy. The Spanish blackout didn't happen by accident. It was the result of a policy that rapidly removed stabilizing elements from the grid without adequate replacement.

How did this happen?

It is interesting to consider how we reached a point where discussing basic engineering realities became taboo. The shift happened gradually. Legitimate concerns rightfully gained prominence but then morphed into an all-consuming lens through which all energy decisions must be filtered.

In this environment, even raising questions about grid stability or reliability was met with accusations of climate skepticism or fossil fuel advocacy.

Many of us — myself included — assumed that grid operators, utilities, and industry would intervene if truly catastrophic policies were being implemented. We trusted that leaders like Angela Merkel and Mark Rutte would get sound advice and make sensible decisions. This faith in technocracy proved misplaced as political imperatives consistently overrode technical concerns.

Why did the simple message that the energy transition would be clean and, at the same time, good for jobs and energy security and growth take hold? Here is my hypothesis (I am writing a paper soon to be out arguing this). Politicians correctly identified that climate, with its slow to materialize and small domestic benefits, is a hard sell in any democratic polity. Voters understand that they can free-ride, and understand that they are unlikely to face themselves the true cost of climate change (which will fall on their children). To successfully push green policy, it was not possible to sell a complicated narrative. The message, as often in politics, became unidimensional: not only was green policy beneficial for the environment, but it would also create green jobs, higher growth, and was generally unimpeachable. Ifs and buts could not be acknowledged, lest voters start doubting a policy considered necessary. It is not a dissimilar story to many that have been at the root of the growing lack of confidence of voters in politicians and experts.

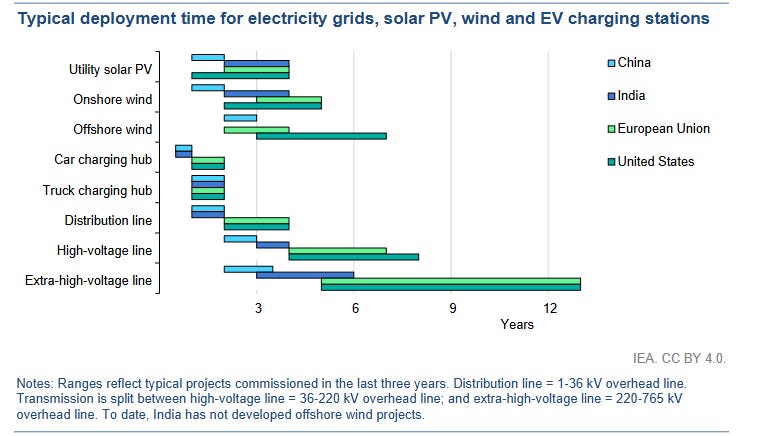

Perhaps Europe's fast transition might have worked if we were faster at building. It is one thing to rip and replace if you build like China today or Europe in the 1960s. But Europe rips before it can replace: coal and gas units close on fixed timetables while grid capacity needed for wind and solar queues stalls. The average implementation time of a transmission project is 10 years (see ACER figure above) Europe has 25000 kilometers of transmission in permitting purgatory. Nuclear power – our one baseload source that is clean – is virtually impossible to build in nearly all of Europe. Between 1977 and 1990 France connected 56 reactors, averaging one completion every three months; since 2000 the entire continent has grid-connected just four large reactors: one in Rumania, one in Finland, one in Slovakia (after 37 years building) and a fourth, in France, 25 years after their previous one. .

We Europeans have laughed at the excesses of American progressives on issues like ‘defund the police’, but on climate policy, Europe went far further than America ever did. On many social issues, US progressives were typically further left than Europeans. Climate is the exception — the one issue where Europe embraced the maximalist position.

Even when Spain sat in darkness, the conversation remained trapped in ideology. Here are Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s thoughts on the crisis: ‘Nuclear power, instead of being a solution, has been a problem’.

In energy, the political center has been missing in action, replaced by a dogmatic fervor where the transition had to proceed at maximum speed regardless of the consequences.

We've committed to targets that would be challenging for countries that can build infrastructure efficiently. The energy crisis demands the same level of attention as defense — perhaps more, given its self-inflicted nature and its impact on growth. Above all, we must return to a debate where engineering and economic reality trumps ideology. Climate change is real and demands action, but that action must work in practice, not just in theory.

I don't think Spain should put the brakes on renewable expansion. The business case for solar is excellent in Spain – way better than in the rest of Europe. The main problem is that Iberia is still functioning like an energy island. It should build more interconnections with the rest of Europe. This should be the main lesson from the blackout: there's plenty of inertia in nuclear France. But just look at the Bay of Biscay interconnector. The project was designated as a Project of Common Interest (PCI) by the European Commission in 2013, and construction only started in 2024, to be finished somewhere in 2028. That's just terrible...

I generally like the content on this blog, but this post draws concerning conclusions from incomplete information. It makes me question the analytical rigor being applied here.

We don't know yet whether renewables were the primary cause of the blackout, or why it cascaded across the entire Iberian zone. Blaming renewables is premature. The grid operators themselves haven't reached definitive conclusions, and the analysis presented here seems to select facts that support a predetermined viewpoint. A large fraction of renewable generation makes some grid contingencies easier to manage and others harder - this nuance is missing from the post.

Likewise, the comments on energy-intensive industries moving abroad lack important context. Gas prices, global competition, and post-pandemic supply chain realignments are much more significant factors than renewable investment in most cases of European deindustrialization. The post presents correlation as causation without addressing these confounding variables.

Finally, the comments about nuclear power are, ironically, purely ideological while accusing others of the same. Most of Spain's renewable capacity was operational again relatively quickly, while nuclear plants typically require much longer restart procedures following a complete blackout. Right now, nuclear generation in Spain is still down 80% from normal levels. I dread to think how long it would have taken to reestablish power in a more nuclear-dependent grid, given the complex restart requirements of nuclear facilities.